EULOGY

ON THE

LIFE AND CHARACTER

OF THE

Rt. Rev. Stephen Elliott, D.D.

BISHOP OF THE DIOCESE OF GEORGIA,

and President of the Georgia Historical Society

BY

HON. SOLOMON COHEN.

Written and published at the Request

OF THE

GEORGIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY.

SAVANNAH :

PURSE & SON, PRINTERS,

MDCCCLXVII.

EULOGY.

One of the most distinguished poets of England has said that ” the proper study of mankind was man,” and I invite you, my friends, this evening, to the contemplation and study of the life, character, intellect, virtues, and high moral culture of one of the remarkable men of our day—the Eight Reverend Stephen Elliott, D. D., and Bishop of the Diocese of Georgia.

Deeply sensible of the distinguished honor conferred on me by the “Georgia Historical Society,” in selecting me to write a ” Eulogy on the Life and Character” of this distinguished Prelate, and painfully impressed with the sense of my want of ability for the proper performance of a duty so important— a task so delicate—I approach its discharge with fear and trembling, and humbly invoke the “Giver of every good and perfect gift,” that He would fill my mind with high and holy thoughts, worthy of the theme, and give me utterance suitable to the occasion.

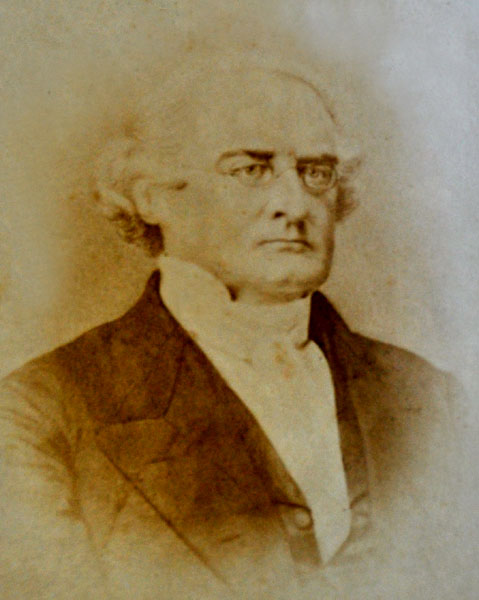

The Rt. Rev. Stephen Elliott

Bishop Elliott was, indeed, a remarkable man ; possessing a very high order of intellect, richly endowed by study and travel; a character chivalric, lofty and commanding; a heart pure, kind and liberal, and adorned with that catholic charity, that appreciation and love of the good and beautiful, that high-toned morality, that trusting faith in God’s word, that obedience to God’s law, that earnest religion that was ingrained in his very nature, that eminently fitted him for the exalted position to which, in the Providence of God, he had been called.

There is an instinct in the human heart that prompts man to seek an honorable fame, and to render himself useful in his day and generation, and it is the peculiar mission of associations like those of the Georgia Historical Society, to perpetuate the memory of the good and great, not only as acts of justice to them, but as incentives to those who may fill their places when they have gone to their reward. The acts, the opinions, the example, of the great and good are heir-looms to posterity, and should be treasured as sacred relics, and with the same reverence that the saint turns to his shrine, so should we regard and venerate those men who, in life, illustrated virtue, have blessed their fellows, have adorned and beautified the sphere in which they moved,. and been worthy stewards of the gifts committed to their keeping. In the contemplation of such a character, we should bring to bear, upon its merits, the best affections of our hearts, and the highest gifts of onr intellects. Man, whom God created in His own image— endowed him with a spark of His own omniscience, and made him but little lower than the angels—must be regarded as God’s vice-gerent on earth. He is the steward of God, who has committed to his care and guardianship inestimable treasures, more valuable than precious jewels and much fine gold—the priceless treasures of an intellect that places him high above all God’s earthly creations—an immortal soul, which is God’s likeness in man, and which may elevate him in eternity to the heaven of heavens, to dwell with His celestial angels, and bask forever in the sunshine of His eternal glory. Such is man— such his duties—such his responsibilities, and happy is that man who, like our departed friend, has acted well his part—has been the faithful steward.

The life of man is like a passing cloud, or in the beautiful language of the Psalmist, it is like grass, “in the morning it flourisheth and groweth up; in the evening it is cut down and withereth,” and though we shall see the departed no more on earth, yet we have the blessed assurance that the illustrious subject of our discourse did, by the purity and beauty of his life, by trustful faith in, and obedience to, a God of hive, prepare himself for the great change from Time to Eternity—from action to reward—for whilst on earth he did “justly, loved mercy, and walked humbly with his God.” He performed, in the language of Israel’s illustrious king, “the whole duty of man,” “he feared God and kept His commandments.”

Death is the heritage of man—it enters alike the palaces of the rich and the hovels of the poor. It drags to the dark recesses of the tomb, the helpless infant, and man in the full strength and pride of his manhood, the delicate maiden, and the hoary head of age, and yet we think “all men mortal, but ourselves.” The daily warnings, that meet us at every step we take in the pathway of life, have no influence on us, and even the fearfully sudden death of such a man as Bishop Elliott has but a temporary effect upon us, like an evanescent summer cloud, that obscures for an instant the brightness of the mid-day sun. It is not my province, nor is this the occasion to elaborate this idea, and press its importance on those who now hear me. But God grant that this fearful visitation, that in an instant, in the twinkling of an eye, has taken from this Diocese its venerated Bishop—from the Church its beloved Pastor—from his family, its father, friend and counsellor—from this community, the bright examplar of a pure, active and blameless life—from our Society, its respected President, and the zealous co-operator in all things tending to its honor and usefulness; God grant, I say, that this fearfully sudden death may not be lost to our eternal welfare, but may teach us, like him, “to do justly, love mercy and walk humbly with our God”—that we, like him we mourn, may be prepared for that awful passage from the beauty and brightness of this world to the gloomy portals of the grave— from trial to judgment—from Time to Eternity. It is no solecism, therefore, to say, that we live in the midst of Death. It is seen, and felt, in all things, animate and inanimate—in the works of Nature and of Art. Death is a resistless power, whose fiat nothing can oppose; a monarch, whose sway is hounded only by that bourne which separates Time from Eternity—Death from Life. I repeat, then, we live in the land of the dying, and well may the weary pilgrim to that region, where there is neither death nor change, exclaim with the inspired Psalmist of Israel, ” I had fainted, unless I had believed to sec the goodness of the Lord in the land of the living.”—Psalm xxvii. 13.

It has been beautifully said, that history is “philosophy teaching by example,'” but how much more appropriately may this remark be applied to biography, or rather to the lives and example of men, like Bishop Elliott, who adorned and beautified every pathway of life in which he walked, and was a living, practical, perpetual exhortation to deeds of goodness, virtue and religion. History deals in generalities—it sets forth great results, public events, and national transactions, on which the destiny of Peoples may turn and be determined—tells of the wrecks and triumphs of Nations and of Races, but gives none of the details, nothing of that inner life of the great actors who produced these results. On the contrary, biography enters, with minuteness, into the private thoughts of individuals, their manners, customs, habits and tempers, and it is these that create, form and direct the opinions and actions of the masses.

Who that ever watched the life and acts of Bishop Elliott; the results of his persevering zeal and energy in all works for the amelioration and improvement of man ; who heard his converse, who listened to his persuasive oratory, and drank from the exhaustless springs of his intellect, ever gushing forth with rich streams, fructifying the heart, the mind, the soul, and elevating it to its eternal source, the goodness, the wisdom, the power of God; who, I say, that has ever basked in the sunlight of his intellect and virtue, that has not felt their ennobling influences, and the purifying results of his unobtrusive piety, and his trustful faith in the God he served ?

Such men, then, as the illustrious Prelate we this day mourn, and are assembled to honor, are beaconlights amid the shoals and rocks of life—they are a “pillar of cloud by day, and of fire by night,” to lead the Israel of God, of every faith, to the footstool of His throne; and, it really seems, when such as these are snatched from us, in the palmy days of their usefulness, that they have been but lent to us, by God, to teach us of the beauty and excellence of heaven. The study of the characters of the good, and useful, of such men as Bishop Elliott ; the examination of their trains of thought, as developed in life ; the recollection of their utterances, their earnest zeal in everything calculated for the temporal and’ eternal good of their race, cannot fail to improve the heads and the hearts of those who may come after them.

The Right Reverend Stephen Elliott, Bishop of this Diocese, was the eldest son of Stephen Elliott, of South Carolina, and Esther Habersham, of Georgia, and was born in the town of Beaufort, South Carolina, on the 31st of August, 1806. The first six years of his life were passed in his native place, but at this juncture, the Legislature of the State of South Carolina established the “Bank of the State of South Carolina”—a purely State institution, based on the stocks and other assets of the State. This Bank was created to afford relief to the planting interest, then suffering from the financial difficulties of the time, growing out of the war with England, and Mr. Elliott, the retired gentleman, the finished scholar, the erudite man, the lover of art, and science, and nature, was called from his retirement to preside over this important institution, and he was re-elected its President, by each succeeding Legislature, during his whole life. This call involved his removal, with his family, to the city of Charleston, and his young son , was placed under the care and tutorship of Mr. Hurlbut, then an eminent teacher in that city. I have been able to learn but little of the early youth of the Bishop. To his biographer this pleasing, and more minute task, will more properly belong, and I fondly hope that our Society will regard it as their peculiar duty to see that the record of his life shall be full and complete. Bishop Elliott was subsequently sent to Harvard, where he remained one year, and was then brought home, to graduate in his loved, native State. This love of his “own,” his “native land,” which prompted this action on the part of bis father, ever filled the heart of the Bishop, animated his actions, controlled his opinions, and was part of his character. And, in the annual address of this Society, delivered by Bishop Elliott a few years after his removal to Georgia, his theme was the cultivation of this home feeling, by every honorable appliance. And I well remember his earnest and eloquent exhortations to love the land of our birth and the home of our adoption—to cherish this feeling—to cultivate, build up, sustain and support home institutions, and how he likened Georgia to the Holy Land of Canaan, “a land of brooks of water, of fountains and depths, that spring out of valleys and lulls ; a land of wheat and barley, and vines, and fig trees, and pomegranates; a land of olive oil and honey.”—Deut. viii. 7, 8.

Graduating with honor, he began the study of the law with the gifted Petigru, whose bright intellect, pure heart, genial nature, and unostentatious charity won the love of all who knew him. The influences of such a parent, and such an instructor, could not fail to make deep and lasting impressions upon a mind and heart like those of Bishop Elliott. He practiced law but a short time—long enough, however, to show that he would have occupied the highest rank in that noble, and time-honored, profession, and long enough, too, to chasten his mind by the severe technicalities and accurate and fine-drawn distinctions of the law. He drank deep of the pure fountains that flowed from the mind of a Coke, a Blackstone, a Mansfield and a Marshall, and in after years, scattered, in that higher and holier field, for which heaven seemed to have destined him, the rich treasures of an intellect thus chastened, purified and enlightened. He soon, however, abandoned the Law for the Church, and sacrificed, to a sense of duty, all the allurements and fascinations of successful political and professional life. He became the humble and unambitious Teacher of Religion, to which he brought the purity of his spotless heart, and all the endowments of his high intellect, and its rich and careful culture. But a short time in his new career had elapsed, when he was called to the Professorship of Sacred Literature, and the Evidences of Christianity, in the South Carolina College. Prior to this, however, he had still further elevated and adorned his powerful mind in the field of critical literature, as a co-editor of the Southern Review, with that gifted scholar and eloquent orator, the late Hugh S. Legare. But higher duties, more serious and arduous labors, were yet to bo assigned to the wonderful man, of whom we now speak. In 1840 he was elected the first Episcopal Bishop of Georgia, the native State of his mother; and in January, 1841, he was consecrated to that high, holy and responsible office. It is not within the scope of an address like this to follow him in his career in the new position to which he had been called. Suffice it to say, that in this, as in every other walk of life he had trod, he brought into successful exertion the best affections of his pure heart, and all the priceless treasures of his rich and cultivated intellect. Under his administration his church bloomed and blossomed like the green olive tree, and spread its branches through the length and breadth of the State. In the midst of this usefulness, when his good deeds and his labors were heavy with ripening fruit, and promised, to him, an abundant harvest, he was, on the 21st December, 1866, called hence to meet his God.

From this hasty and concise sketch, it will be seen that when this great man was called from his labors on earth, he had not yet reached ” the days of the years” of man. His noble form—the fit receptacle of his pure soul, and polished intellect— seemed to promise a long life of physical vigor and moral usefulness. But death ever loves a shining mark, and heaven claimed him for its own. And yet his could scarcely be called Death. It was a translation from Earth to Heaven; from Time to Eternity. The portals of the mansions of the blessed were opened, and no lingering sickness, nor torturing pain, stayed his transit to the realms of eternal bliss.

“And Enoch walked with God, and was not, for God took him.”—

Genesis V. 24.

Bishop Elliott was ever anxious for the welfare, the improvement, the moral culture of his kind, and particularly of his well-beloved South—a land which he loved with all the energy of his mind, and the purity of his heart. It had his best affections, and his ever watchful care for its welfare. He had not long been a resident of Georgia, when, with that far-seeing wisdom, which was a prominent characteristic of his exalted intellect, he determined to establish a school in middle Georgia, for the training and education of the girls of the State. He well knew, and justly appreciated the powerful influence of woman in all things tending to man’s present and future welfare and happiness, and he watched and guarded the infant institution with the care and tenderness of a mother. The education of woman—the formation of their characters—the purifying of their hearts, and the enlightening of their minds, so as to fit them for the high and holy duties of their station, is the greatest boon that can be conferred on any people. It is in the hands of woman that man’s destiny rests. As the mother of our children, their friend and instructor, she may be regarded as the disseminator of that intellectual morality and political civilization which are the corner-stones on which rest the grandeur, the power, the prosperity and true glory of mankind. The education of woman is a necessary element of an advancing civilization, and if we desire that society should be refined, enlightened, and moral; that it should contain the seeds of a progressive civilization, we must look for these results to the thorough education of woman. Bishop Elliott saw and felt all this, and in the true spirit of a patriot and a man of God, he put his hand to the work with the energy of his noble mind, and the warm affections of his pure heart. In this same spirit he, in conjunction with his dearly cherished friend, the late Bishop Polk, of Louisiana, and other Prelates of his Church, planned, and but for the cruel war waged against the South, would have carried out, that grand and noble institution, “The University of the South.” With untiring zeal, and well-directed energy, these two noble men laid the broad foundation of that moral and intellectual work which will yet spring into life, activity and usefulness—a splendid monument of the far-seeing intellect and pious enthusiasm of these truly Southern men, and watchful guardians of Southern welfare. No, the “University of the South” must not die. It must rise and live, as enduring as the eternal hills, and from its halls it shall send forth fertilising streams of literary and moral culture. Her Alumni shall yet fill every walk of life, blessing and blest, and an eternal halo shall rest upon the names of Elliott and Polk. How touchingly beautiful was the love of these two illustrious men—their souls were knit together. There was between them a unity of thought, of feeling, of action, all beautiful, all pure. Like unto Saul and Jonathan, they were lovely and pleasant in their lives, and even death could not separate them. Men and women of the South, weep over the graves of these faithful guardians of your most precious treasures, and teach your children’s children to rise up and “call them blessed.”

Bishop Elliott was eminently endowed with all the physical and moral attributes of an orator. A tall, commanding and majestic figure—the very impersonation of the Priests and Prophets of the past—a mild, impressive and graceful delivery; a clear, solemn and finely modulated voice; a gentleness, yet appropriateness of action, that beautifully accorded with his benignant expression of countenance, and the sacred calling to which all his powers” were devoted. He possessed also the rare gifts of deep thought—exhaustless treasures of available learning— the power of giving utterance to his thoughts in a purity of language, a cogency of reason, a beautiful order, and classical arrangement of the prominent points in his discourses, and all of these were adorned by a matchless flow of oratory, and a dignity of action that marked him as the child of genius, eloquence and learning. In his sermons there was no rant, no denunciation. There was one continued stream of mild, persuasive eloquence, close reasoning, and beautiful and heart-touching displays of the excellence of virtue, and the necessity and priceless value of religion. He had a clear judgment, a pure heart, and that tact, or knowledge of human nature, and the motives of human action, that enabled him to carry conviction to the heads and hearts of his hearers. His language was peculiarly choice, drawn from the well of pure “English undefiled” ; and his mode of stating his points and arranging the arguments in their support, were stamped with that order, system, and clear, legal technicality, with which his mind had been tutored when, in the threshold of life, he had stored it with the rich treasures of legal lore. So, too, had he drawn deeply from other sources, whence the human mind nurtures and adorns the immortal spark with which God has blessed mankind. He was a fine classical scholar, and thus the “mental treasures, and sparkling wit of Greece and Rome, were his also. His intellect had been chastened, purified and exalted, when engaged in the pursuit and study, and in the exercise of classical criticism. Indeed, he drank in knowledge from almost every fountain, and was ever ready to scatter and disseminate the priceless treasures of his intellect for the good and improvement of his fellow-creatures. He was indeed a rare combination of mental and physical strength, power and grandeur. Tall, well-proportioned, and with a native majesty and dignity that ever commanded respect, and yet a gentleness and amenity of manner that won our love. There was no assumption about him, no pedantry of manner or of words. All was simple, grand, majestic; and yet he was ever ready to pour out, to all inquirers, the information he had garnered from every field of science and literature. He had a fund of knowledge on every subject, and he was lavish in its distribution. The true character and intrinsic worth of a man’s mind and heart are, unquestionably, more fully developed in the unrestrained, and familiar intercourse of social life, than from any evidence exhibited in the discharge of the higher and more solemn duties of man’s career. In the former all restraint is thrown aside, and the innate man is displayed in all its truthfulness, simplicity and purity. It was in this unrestrained intercourse that the character, and heart, and mind of Bishop Elliott shone forth in all the mild excellence of his gentle nature. Here, too, with unaffected ease, and the simplicity of true genius, he lavishly distributed the rich gems of his highly cultivated intellect. There was no dictation, no affectation, no vain exhibition of display , all was plain, and simple, but full of knowledge and instruction. All of us, of this Society, must remember, with tender feelings of love and gratitude, those delightful meetings under his Presidency, when his suggestive mind was ever throwing out hints for improving our usefulness, and disseminating the lights of science and literature.

And now all this worth, this excellence, this purity, this knowledge, this exalted piety, lies in the dark and silent tomb, and we are left to mourn. His immortal spirit has gone to the God who gave it, but his good deeds live after him, and to us they are a rich legacy, a priceless treasure, that we should guard with holy zeal; a shining light, that should lead us onward in the paths of virtue, religion, science and literature; paths of pleasantness and peace, in which he walked with piety and dignity, and scattered blessings as he went along. His example is the “silver lining” to that cloud which his death has cast over our hearts and homes.

The whole South mourns him—the State weeps for him—his Church and Diocese cry aloud in anguish, and his loved and cherished lamily “sit solitary”— their harp hangs upon the willow, for their home is desolate—their “silver cord is loosed,” their “golden bowl is broken.”

But I repeat, his example is left to us, and whilst we mourn we must cherish the memory of his worth, and strive to emulate it. We must bow, with submission, to God’s will, and from the depths of our stricken hearts, in the spirit, and trusting faith that animated his life, exclaim, Thy will be done.

Bishop Elliott’s grave is in Savannah’s Laurel Grove Cemetary.