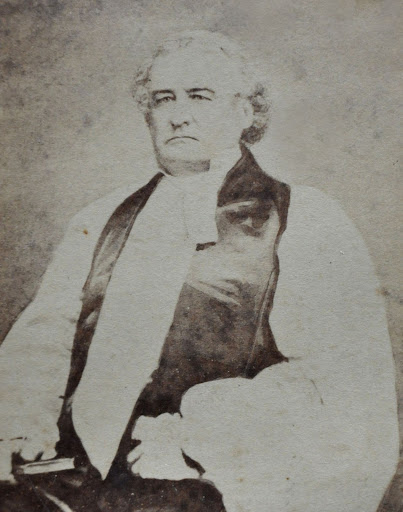

A Sermon by Bishop Stephen Elliott Jr. preached in Christ Church, Savannah, on Friday, March 27th, 1863, for the Day of Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer appointed by the President of the Confederate States. The note which proceeds the sermon shows the liturgical context for this sermon.

To the Clergy of the Diocese of Georgia.

The President of the Confederate States having issued his Proclamation appointing Friday, March 27th inst., as a day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer, and inviting the people of the said States “to repair on that day to their usual places of public worship and join in prayer to Almighty God, that he will continue his merciful protection over our cause; that he will scatter our enemies and set at naught their evil designs, and that he will graciously bestow to our beloved country the blessings of Peace and Security.”

Now, therefore, I, Stephen Elliott, Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Georgia, do direct the Clergy of said Diocese to assemble their congregations upon that day, and to keep the Fast with thankful hearts, and with broken and contrite spirits.

Upon the occasion of the Fast, the Clergy will use the following service:

- Morning Prayer as usual to the Psalter.

- Psalms of the day, 3d, 7th, 34th.

- 1. Lesson. Nehemiah, ch. IV.

- 2. Lesson. Matthew, ch. VI.

- Use the whole Litany.

Immediately before the general Thanksgiving, introduce the Confession which precedes the Epistle in the service for Ash-Wednesday and the following prayers:

PRAYER.

O most mighty and gracious God, thy mercy is over all thy works, but in special manner hath been extended towards us, whom thou hast so powerfully and wonderfully defended. Thou hast showed us terrible things that we might see how powerful and gracious a God thou art; how able and ready to help those who trust in thee. We therefore present ourselves before thy Divine Majesty to offer a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, for that thou heardest us when we called in our trouble and didst not cast out our prayer which we made before thee in our past distress. And, we beseech thee, make us truly sensible now of thy mercy as we were then of our danger; and give us hearts always ready to express our thankfulness, not only by words, but also by our lives, in being more obedient to thy holy commandments. Continue, we beseech thee, this thy goodness to us, that we, whom thou hast saved, may serve thee in holiness and righteousness all the days of our life, through Jesus Christ our Lord and Saviour. Amen.

PRAYER.

O most mighty Lord God, who reignest over all the kingdoms of men; who hast power in thy hand to cast down and to raise up, to save thy servants and rebuke their enemies, let thine ears be now open unto our prayers and thy merciful eyes upon our trouble and our danger. O Lord, do thou judge our cause in righteousness and mercy, and wherein-soever we have offended against thee, or injured our neighbor, make us truly sensible of it and deeply penitent for it. We humbly confess that we are unworthy of the manifold goodness vouchsafed us in the struggle for our rights, yet we are bold, because of thy long suffering, to pray for the continuance of it and to supplicate thy blessing upon us and our arms. Cover the heads of our soldiers in the day of battle, and send thy fear before them that our enemies may flee at their presence. Establish us in the rights thou hast given us, in our Government and in our Laws, in our Religion, and in all our holy Ministries. The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, but our trust is in the name of the Lord our God. Hear us, O Lord, for the glory of thy name and for thy truth’s sake, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Given under my hand this twenty-first day of March, A. D., 1863.

STEPHEN ELLIOTT,

Bish. Prot. Epis. Church, Diocese Ga.

A Sermon.

JUDGES: CHAPT. XIV, vv. 12, 13, 14.

12. “And Samson said unto them: I will now put forth a riddle unto you; if you can certainly declare it me within the seven days of the feast and find it out, then I will give you thirty sheets and thirty change of garments.

13. “But if ye cannot declare it me, then shall ye give me thirty sheets and thirty change of garments. And they said unto him, Put forth thy riddle, that we may hear it.

14. “And he said unto them, Out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong came forth sweetness.”

There has been for some time past a deep and wide spread yearning for peace. It has exhibited itself in the greediness with which the people of the Confederate States have listened to every rumor of intervention that has floated across the Atlantic, and in the credulity with which they have believed that the recent political movements in the United States meant anything more than the customary struggle for power. It is a natural yearning, especially in a people unaccustomed as we have been to a state of warfare, for the human mind abhors anxiety and doubtfulness, and shrinks from a condition of things which forces it to live entirely in the present and for the present. With a war pressing upon us which is continually changing its features and enlarging its proportions–to-day a war for the Union, and to-morrow a war for emancipation–now waged with the power of an ordinary government, and then with forces almost unprecedented in modern history–there is for us not even a conjectural future. We can form no plans of life, nor look with reasonable probability upon the results of any undertaking. Our households are kept in perpetual agitation–our pursuits are irregular and anomalous–our feelings oscillate between excitement and depression–our affections are ever on the rack of cruel suspense. Under conditions like these the mind and the heart will both long for peace; for rest from an excitement that is wearing them out; will crave, if only for a little while, a recurrence of those days, when the sound of war was not heard in the land, and when the sun did not cast its setting rays upon fields of blood and carnage.

But this yearning for peace has no smack of submission in it. That has not entered into the thoughts of any body. It is really nothing more than a natural wish that an useless strife should cease; an earnest desire that a struggle should be ended, which can end but in one way. When the peace which is longed for is embodied in words, it invariably includes the ideas of entire independence and complete nationality– independence from all the bonds, whether political, commercial or social, which have hitherto hindered our development–nationality, with our whole territory preserved to us, and with no entangling alliances binding us for the future. This is its whole scope and meaning, and is very distinct from any such fainting of the spirit as would precede submission. It is rather the token of a restless energy, which pants to enter untrammeled upon that new career of freedom which it is working out for itself, and which seems to rise before it in brightness and grandeur, and to beckon it onward to glory and happiness. The courage of the Confederate States is not failing, but its passive endurance is sorely taxed, and like a beleaguered lion, it chafes against the restraints which keep it from its native haunts, and rages because it cannot at once strike to the earth all the enemies who encompass and goad it, even while they can never either destroy it or make it captive. With a bound and a roar, the Lord of the forest will one day break through the hosts which surround him, but until his opportunity comes, he must bide his time and be satisfied with striking terror into his hunters by the lessons which he may give them, of his fierceness and energy.

But this yearning for peace has no smack of submission in it. That has not entered into the thoughts of any body. It is really nothing more than a natural wish that an useless strife should cease; an earnest desire that a struggle should be ended, which can end but in one way. When the peace which is longed for is embodied in words, it invariably includes the ideas of entire independence and complete nationality– independence from all the bonds, whether political, commercial or social, which have hitherto hindered our development–nationality, with our whole territory preserved to us, and with no entangling alliances binding us for the future. This is its whole scope and meaning, and is very distinct from any such fainting of the spirit as would precede submission. It is rather the token of a restless energy, which pants to enter untrammeled upon that new career of freedom which it is working out for itself, and which seems to rise before it in brightness and grandeur, and to beckon it onward to glory and happiness. The courage of the Confederate States is not failing, but its passive endurance is sorely taxed, and like a beleaguered lion, it chafes against the restraints which keep it from its native haunts, and rages because it cannot at once strike to the earth all the enemies who encompass and goad it, even while they can never either destroy it or make it captive. With a bound and a roar, the Lord of the forest will one day break through the hosts which surround him, but until his opportunity comes, he must bide his time and be satisfied with striking terror into his hunters by the lessons which he may give them, of his fierceness and energy.

But God has thought it best for us that this cruel war should endure yet longer and should be waged with an increased ferocity, if not with augmented forces. Our sins are to be more heavily punished, at the same time that our faith is to be more thoroughly sifted, and our submission to his will made more complete and perfect. The causes which led to this war–many of the circumstances which have accompanied it and the marvellous manifestations of himself which God has made throughout it–the mighty interests of a moral and religious nature which are bound up in its results–all forbid us from looking upon it as a mere conflict for power. We must take the Divine will into all our reasonings about it, and our humiliation to-day must occupy itself in helping us to school ourselves into an acquiesence with his divine arrangements. We may feel sure, seeing how visibly he has fought for us–how strikingly he has supported us through our hours of mortal peril– how he has strengthened us in our weakness, and comforted us in our desolation–that whatever he may order for us in the conduct of this struggle, shall be for our ultimate blessing, and that we ourselves shall one day see it and confess it. It may be a bitter disappointment to us that the dove has returned to the ark without the olive leaf in her mouth, thus notifying us that the waters of strife have not yet subsided, but the ark is still in safety and under the guidance of Him whose eye never sleepeth and whose love never faileth! Let us, then, resume our sacred work of stern resistance; let us pray for fortitude, for patience, for endurance, for faith; let us be satisfied that there are lessons of deep moral import which are yet to be evolved from the continuance of this struggle, and we shall discover in God’s own time that “out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong came forth sweetness.”

There is something very delightful in this word Peace. It strikes upon the ear of a tumultuous and ever agitated world with a musical softness that is wonderfully attractive. We associate with its presence, comfort and ease and prosperity and love. All that is brightest in the home and in the heart is wrapped up in it. The pictures of fancy, the dreams of poetry, the richest promises of the gospel are all woven out of its golden hues. The sequestered valley, with its murmuring stream and its quiet happiness–the cultivated plain, basking in the sunshine and covered all over with the luxuriant harvest–the crowded city, as it lies asleep under the soft moonbeams, its hum of industry stilled by the inexorable decree of nature–the placid waters, reflecting as in a mirror, the softened forms of the huge monsters which, when awakened from their slumbers, are to bear across the ocean the products of the earth–are some of the scenes which we have been accustomed to harmonize with the idea of Peace. And when we have enlarged the scope of our vision, and risen upon imagination’s airy wings, we embrace in the same idea of Peace an interchange of kindly affections among all the nations of the earth, and an universal good will towards men. Philosophy and poetry and prophecy have all combined to body forth its blessings and have alike personified it on earth and in heaven by the mild eye and the gentle murmur of the Holy Dove.

But delightful as is the word, and attractive as are its associations, we should not be seduced by them to yield up either right or truth or justice for its attainment. It would indeed be a great burden rolled from our hearts if we could take our children to our bosoms, and feel that they indeed had a country–if we could look upon our noble sons and rejoice that they were freed with honour from any further conflict with foemen so unworthy of their steel–if we could glance around our hearthstones and be satisfied that no rude trumpet would again disturb their peace, no roar of cannon drive us from their shadow–if we could enter the temples of God and sing the angels song of peace on earth, good will towards men. But until we can do so with honor and with security, let us banish the idea from our thoughts. Let there be no making haste to find Peace. It will come when God sees that war has accomplished his purposes, and it ought to come no sooner. Unless we follow his guidance in this matter, we shall fall into temptation and a snare, and in grasping at a shadow, lose the substance which we have already gained at the cost of so much precious blood. We seceded from the Government of which we were once a part, because we felt that under it we no longer had a country. For what is our country? Our country is in its constitution, and its provisions were openly and shamefully violated–our country is in its religion, and its altars were desecrated by infidelity and the vilest fanaticism–our country is in its institutions, and they were threatened with total subversion –our country is in its social life, and that was covered all over with rude abuse and malignant defamation. And shall we, for peace sake, think for a moment of returning to the embrace of such an Union? God forbid! Let us learn at once the stern truth that we have no country until we make one. We can never go back to that whence we came out. We should not recognize it in its present garb of tyranny. We should not discern that once proud Republic under the mask which it now wears, with the oriental despotism that rules over it, and the oriental submission that kisses its feet. In its delirium it has lost all sense of regulated liberty–it remembers only passion and vengeance. Closing its eyes against all truth, and shutting its ears against all wisdom, it is striking at man madly in its rage, and it is cursing God who has placed the bit in its mouth, and is saying to it, “Thus far shalt thou go and no further.” In quietness and confidence is our strength. Manly fortitude and heroic patience will accomplish for us in due time all that we are contending for. We did not enter upon this conflict in the temper of children, who were quarrelling for some mere point of pique, but with the resolution of men who perceived that every thing which made life tolerable was trembling in the balance. Let peace come to us, and let us not forget our manhood and go in search of peace. We might find a counterfeit of it among the contrivances of man and meanwhile lose that heaven-descended peace which God will give us, if we will wait his will and abide his discipline. Every thing forbids us to be too solicitous for peace. Our consecrated cause–consecrated by the blood of our children–the aid and comfort it would give our enemies–the permanent welfare of our posterity. If God sends it to us, then welcome, bright-eyed Peace! but woe to us if, for its sake, we sacrifice one jot or one tittle of our duty and of eternal justice!

In the present condition of things such a peace as we ought to accept would be impossible. What have we to offer in exchange for all the territory which the enemy now holds within the borders of the Confederate States, for the half of Tennessee, for the Eastern and Western regions of Virginia, for all our rich sea-coast, for our harbors and forts, for that garden spot of our country, lovely Louisiana? What have we, at the present moment, to cast in the balance against Maryland and Kentucky and Missouri, whose right to determine their own future destiny, it would be base in us to abandon? Hence is it that foreign mediation would be, at this time, and under our present circumstances, so disastrous to us, and hence is it, I firmly believe, that God has put it into the heart of our enemies to reject it. What could foreign mediation effect? What could it propose as the basis of settlement, but some such terms as European diplomacy has been conversant about for ages? Would you consent to peace upon the terms of the uti possidetis, each party holding what it possesses? Your own solemn legislative pledges cry out against it. Virginia would blush for shame at such a proposition, and would weep, as Rachel, for her children, refusing to be comforted. Louisiana would lift her saddened eyes and fettered arms and plead for mercy and deliverance. The home of Jackson would burn with indignation that the ashes of her unconquered hero should be trampled upon by hirelings and slaves. Old ocean would murmur curses against you upon her wailing winds, and would lash your shores in fury at their degradation. Would you grant to your unscrupulous enemies special commercial advantages and a favored intercourse? This would hold us in as utter vassalage as we have heretofore been held, would ruin our revenues and make us tributary forever to Northern industry. Would you pay money for peace? At such a thought, the shade of Pinckney would arise from its dust, and bid you remember what Southern spirit was, when he uttered the immortal words, “Millions for defence, but not a cent for tribute.” Mediation can do us now no good. It might embarrass us and place us in a false position before the world, but it could not advance us one step towards an honorable peace. Let us then give thanks this day to God for having so hardened the heart and blinded the eyes of our enemies as to induce them to repel their best and truest friend in his advances for their relief.

But besides mediation, there is another movement of Foreign Powers upon which many have rested their hope for peace, recognition, followed by forcible intervention in our behalf. If such a hope had ever any basis of reality, it is now, in my opinion, forever put at rest by the recent outbreak in Poland and its rumored extension to Hungary. Revolution, and European cabinets will consider our movement to be revolution, has had no friends among the crowned heads of Europe since the convulsions which have swept over their dominions again and again since 1789. It is an infection which they dread. It rises before them perpetually like a fearful spectre, and sits with them at their feasts and troubles their hours of sleep. They have acquiesced, ’tis true, from time to time, in changes of dynasty; they have, under very peculiar circumstances, and when the pressure of danger was at their own doors, as in the cases of Belgium and Italy, intervened and saved themselves from internal discord, but the general action of the European powers has been adverse to the early recognition of Governments founded upon revolutionary movements, and especially to any thing like an armed intervention in their favor. The revolt from Spain of her South-American Colonies began as early as 1810, and although largely assisted by English capital and English muscle, they were not recognized by the government of Great Britain until 1823. Mexico declared her independence in 1813, and it was not until 1825 that she was welcomed into the family of nations. But the most striking example of modern times is that of Greece. If there was any people whose struggle for independence should have met an instant and enthusiastic response in every court of Europe, whose earliest movements should have caused every heart to bound with joy, and every sword to leap from its scabbard, it was that of the Greeks. They were the pure descendants of the old Hellenic race, whose history was a household word in every abode of civilized man–whose philosophy had given tone and direction to all the thought of the modern world–whose literature had awakened Europe from its sleep of centuries, and had irradiated its darkness with light and beauty. Though dead themselves, their voices had been speaking from their graves and animating the nations to a lofty ambition in arms and letters. They were, moreover, Christians, contending against the ancient enemies of the faith, and calling upon the Church of the living God to lift the banner of the Cross once more in conflict with the Crescent. Hear their own eloquent appeal to the Congress of Verona, made in the second year of their struggle: “The sentiments of piety, of humanity and of justice by which this assemblage of sovereigns is animated, inspire the Government of Greece with the hope that its just demand will be favorably listened to. If, contrary to all expectation, the offer of the Government should be rejected, the present declaration must be considered a formal protest which Greece lays this day at the foot of the Throne of Divine Justice–a protest which a Christian people addresses with confidence to Europe and to the great family of Christianity. Weakened and worn out, the Greeks will then place their hope only in the strength of God. Sustained by his all-powerful hand, they will not bend before tyranny; Christians, persecuted through four centuries for having remained faithful to our Saviour and to God our Sovereign Master, we will defend, even to the last, his Church, our fire-sides and our tombs; happy to descend into them freemen and Christians, or to conquer, as we have hitherto conquered by the alone strength of our Lord Jesus Christ and by his Divine power.” And what was the response of this Congress of Sovereigns? A cold denial even of recognition; an utter refusal to give any countenance to this illustrious people who had sprang, as if awakened by some new Tyrtæus, into the arena of nations, and were fighting upon the very battle fields which Leonidas and Themistocles had made immortal. It was not, until with a heroism worthy of their race and an endurance which would have illustrated martyrs, they had waded through seven years of the fiercest warfare–through seven years of fire and blood and massacre–through seven years of appalling misery such as we have not yet dreamed of–that the selfish hearts of the nations would listen to their cries, and deliver them from the brutal ferocity of the Mussulman! Should we, in the face of such examples, lean upon any such hope as foreign intervention? It was well, perhaps, ere we had become conscious of our internal resources, that the public mind should have been flattered with such a delusion. Possibly it encouraged some who might otherwise have fainted in the hour of our weakness, but now, when we have aroused ourselves like a strong man from sleep, and such a reliance is no longer of any consequence to us, it is well to say that we should never have looked for it. Any such expectation was contrary to the lessons of history, and was rested upon grounds which have proved themselves utterly fallacious.

There are but two sources whence we may look for such a peace as we should be willing to accept–a rupture between some great naval power and the United States, which would permit us to recover our sea-coast, together with our cities, harbors, and ports, or a civil war among the remaining States, which would occupy our adversaries at home, and enable us to expel them from our territories. When either of these contingencies occurs, then may we hope for peace; then may we begin to sing our song of deliverance. But not until then. What the probability is of either of these events, you can judge as well as myself. They are both in God’s power to bring about naturally, whenever it pleases Him, and in my opinion he is gradually leading up our enemies to this catastrophe. The little cloud, like a man’s hand, arising out of the sea, is beginning to show itself, and their heavens may soon be black with storm and wind. This is clearly, in my estimation, the next manifestation which God will make of Himself in this conflict. But, like the prophecies of Scripture, so are these movements upon the stage of the world. We may understand what is the coming event which is to be evolved from the curtained future, but we cannot always reckon the time which that event will consume in its complete development. Time, in God’s view, is very different from time in our view. A thousand years are with Him as one day, and one day as a thousand years. That our enemies are advancing, step by step, to a deep and bitter humiliation, I feel no doubt, and never have felt any; but how long a period may be required by God to bring them into the position, when it shall work upon them the moral discipline it is intended to produce, or for how many years our sins may delay our deliverance, are points which no man can certainly know. The Israelites were kept forty years in the wilderness, because they needed that discipline. And when I perceive the love of money which is rapidly pervading the Confederate States–that love of money which the Apostle calls the root of all evil–I tremble lest we shall yet be pierced through with many sorrows. It is sad to think how a noble cause, which should fill the whole heart, and absorb all the energies of our people, is embarrassed and may be sacrificed by a spirit of covetousness, the lowest and meanest of all decent passions, and which God ranks in his holy Scriptures alongside of uncleanness and idolatry. Is this a time for you, O citizens, when our gallant soldiers are breasting with their indomitable valor the flood of iniquity and desolation which is threatening to involve in one indiscriminate ruin your homes and your altars, to be filling their hearts with anxiety about the loved ones whom they have left behind them? to be reducing, through your unwise speculations and silly competitions, the comforts of your defenders to the very lowest point of subsistence? If you will prey upon one another, for God’s sake do not prey upon the soldier. Let him be an exception to your scale of prices. You satisfy your consciences by whispering to them that the price of everything has risen alike, and that, to protect yourselves, you must sell at extravagant prices, because you buy at extravagant prices. But remember that the pay of the soldier does not increase; that his little pittance remains the same, while your charges upon him are increasing with strides so enormous that imagination can scarce keep pace with them. And remember, also, that this unnecessary elevation of prices prevents the Government from increasing that pay, because any enlargement of its expenses would only further depreciate the currency, and would ultimately force the Government into a collision with its people, which is most sincerely to be deprecated, or would compel it to give up the struggle in despair. A country can never be conquered so long as its people are unselfish and self-sacrificing, but when the cause is forgotten in the mad hunt after money, then the eye becomes dim, and the arm falls nerveless. “It becomes,” as Isaiah says, “a people of no understanding: therefore, He that made them will not have mercy on them, and He that formed them will shew them no favor.”

There is no prospect, then, before us, but the prospect of continued war, while God is working out for us our deliverance. Peace cannot come to us now, so far as man can see, save through the course of events which we have just detailed. With God, of course, all things are possible, and He can, if He chooses, produce such a change in the hearts and feelings of our enemies as to cause them at once to desist from their unjust invasion of our homes and firesides. But as He always acts through natural means; always works out His purposes by a sequence of events which are entirely within the scope of unbelief to consider as customary, we can scarcely hope for such a divine intervention. Nor will our consciences permit us, at this moment, to feel that we deserve it. We must therefore submit to God’s will, and become learners once more in the school of war. We are not morally prepared for peace and prosperity, for as soon as God turned the tide of victory in our favor, we set our hearts upon covetousness, and fell down to worship the golden calf. Let us endeavor, then, to understand the lessons which are wrapped up for us in the experience of this war, so that “out of the eater may come forth meat, and out of the strong sweetness.”

War is a great eater, a fierce, terrible, omnivorous eater. It eats out wealth, property, life–it devours cities and nations–it tears to pieces laws and institutions, and scatters their fragments to the winds–it consumes comfort, and happiness and joy–it lacerates the feelings and the affections–it devours religion, and tramples under foot its temples and its altars–it rides in desolation upon the storm of passion and the whirlwind of vengeance. It is classed by God with famine and pestilence, among His sore judgments, and when He would threaten His people cruelly, He threatens to bring the sword upon them. The blood of man is counted in the Bible as a most mysterious agent, crying from the earth against him that spilleth it, and polluting the land upon whose skirts its drops are sprinkled. And yet with all this, as God’s means of discipline, it has its moral and political lessons, and God is keeping us perchance under its cruel yoke that we may learn them ere we assume our place among the nations of the earth.

Heraclitus, one of the wisest of the Greek philosophers who preceded Socrates, carried this view of the value of war as a teacher and a producer to such an extent, that he advanced it as one of his aphorisms, and left it as a legacy to Greece, that “War was the father of all things” *(Πολεμοζ πατηρ παντων).–that all things are evolved by the strife of antagonistic forces. Even under the revelation of God this is a very manifest truth in many particulars, and we can very well understand how one who looked out upon the world–the natural as well as the moral world–without any heavenly light to guide him, or any divine voice to teach him, might consider this strife as the law which God had impressed upon His creation. He perceived everything to be at war–cold with heat–light with darkness–evil with good–conscience with passion–barbarism with civilization–and out of this strife to come all the progress and all the blessing which the world then knew. Could he have known the sublime truth, of which his contemporaries, the prophets and kings of the Jewish dispensation, had been darkly informed by prophecy, that truth and salvation were to be evolved out of the warfare between Christ and that “arch angel ruined,” he might well have considered his aphorism as including divine as well as human things. And while I would apply it in a very restricted sense, to the wisdom which may be gained from the warfare of nation with nation, I am satisfied that it is quite as true in that connection, as in its application to physical or moral strife.

Peace is not always the safest condition which a fallen being can enjoy. There may be a cry of peace, peace, when there is no peace; a long prosperity, during which there may creep over us an entire relaxation of moral principle, in which all the energy of virtue may die out, and truth herself be obscured under the sophistry of appearances. Under this condition of things, the wholesome discipline of adversity is the very kindest application which God can make to our necessities, for it at once tears the mask away from things around us, and points us to the stern reality of life. If we be true at heart–if the corruption has not extended to the core–we may be saved, for the struggle then begins between truth and error, and, by the help of God, the right becomes triumphant, and we attain a wisdom which goes with us through life. And as with the individual, so with nations. A peace without interruption engenders vices which, unless checked, lead rapidly to corruption and decay. Prosperity follows peace, and wealth prosperity, and luxury wealth, and moral degradation luxury, and thus this greatest blessing of God, if man could rightly use it, is transmuted, through the inevitable alchemy of sin, into its corresponding curse. The civil state needs continual agitation and fresh infusion of virtue from the chastisements of God, just as a lake needs the purifying winds of heaven, and reviving waters from the fresh springs of nature. Without conflict and chastisement, there is but little exercise for the higher energies of man, whether intellectual or moral, and but little scope for the nobler characteristics of self-denial and self-sacrifice. The old Roman virtue, which has passed into a proverb, and which was certainly the best development of national life which the world had known, before Christian civilization refined and perfected it, was built up out of this continued strife with adverse circumstances, and did not decay until she had conquered the world. Without this conflict in the formation and growth of a nation, effeminacy creeps in–public virtue becomes enervate–the spirit of a people exhales, even while the forms of its government are preserved. I need not refer you to our own unhappy republic as an illustration of this truth.

The meat which we are bringing forth out of this fierce eater, War, is strong and wholesome, but not always palatable. It is, in some respects, rather humiliating to our conceit, and derogatory to our foresight. But it is well for us to look the truth at once in the face, and to learn as soon as possible our national experience. It will be a most happy circumstance if we can enter upon our career as an independent power upon right principles, and not be compelled to retrace our steps through sorrow and suffering. If out of the strong wrestlings with adversity we can bring sweetness for our children, we may go to our graves with thankful hearts, and be sure that their blessings will fall thick upon our memories.

At the commencement of our revolution, and for a long time prior to it, we were boasting that we held the civilized nations of the earth, and especially England and France, the leading powers of Europe, in such bonds of dependence upon us, that they could never permit any war which shut them out from our staple productions, to continue for any number of years. We believed very sincerely that the cotton interest constituted so large a portion of their manufacturing and commercial wealth, that any serious interruption of the supply would create not only great distress in those countries, but would perhaps produce revolution. Under this delusion we continued for eighteen months after our movement began, and it is not yet entirely dissipated. It will require at least two years more of British endurance to convince us of our mistake, but we are, nevertheless, learning our lesson by degrees. We are finding out that God does not permit, under his Providential arrangements, any one nation to hold in its hand the fate, or even the destiny of other nations, but that climate, soil, labor, staples, are so distributed throughout the world, that if a supply of any necessary article is dried up in one direction, its production can be forced in some other direction. That we hold great advantages over any other portion of the earth in the growth of our great staples, no one can deny. We can defy competition, because of the peculiar conditions of our labor and climate, but we cannot rule the world as we once conceived that we could. Indeed, it becomes a serious question whether our blockade is not playing into the hands of British statesmen, who have long desired to be freed from the dependence upon us under which they have writhed for so many years, and which has again and again induced them to submit to aggression on the part of the United States. They hope, under the stimulus of high prices, and of necessity, to engage other countries, and especially their own colonies, in the culture of cotton, and thus carry to perfection their vast colonial system. We must dismiss this idea, and prepare ourselves to enter heartily and generously into the social life of the world, and give and take as the rest of the nations give and take. And it is a most important lesson for us to learn at once, for it will make us understand the necessity of diversifying our pursuits, and of strengthening ourselves against the domination of foreign powers. Had we entered upon our career as an independent people without the lessons of this war, we should have been introduced into life with all the coxcombry of youthful conceit, and should have found out in another way, that cotton was not king, and that other nations had weapons more efficacious than staples with which to meet our pretensions. We shall now, I trust, take our place among the nations of the earth with the manly maturity of experience, fully sensible of the value of our resources, but not flaunting them forever in the face of the world, and properly prepared to defend them with an army and a navy which shall command the respect of the world, while they shall not tempt us to foreign aggression. This is one piece of wholesome, though not palatable meat from the mouth of the eater.

When we entered upon this struggle, all of us were advocates of a system of free trade with the world, which, if adopted, would forever have confined us to agricultural pursuits, as the single channel of our industry. The condition to which tariffs under the old Government had reduced us, produced in us an intolerable aversion to all restrictions upon trade, and drove us, at one period, into forcible resistance to their extension. And this was all right under the circumstances in which we were then placed. So long as the duties upon imports affected mainly our interests, and the money collected by them was distributed in another section of the Union, it was for us an emasculating process, which was fast exhausting us. We were really nothing more than hewers of wood and drawers of water under the workings of the Government of the United States. But the pressure of this war is teaching us new ideas upon this subject, and is bidding us beware how we ever permit ourselves to be caught again, as we now are, without clothing, and shoes, and iron, and salt, and the absolute necessaries of life. Free trade is well enough in regard to those articles which are luxuries, but it should never prevail so far as to make us dependent upon other nations for those things which a people must have, under any circumstances, whether of peace or of war. Luckily for us, this war will force upon us such duties, for revenue sake, in order to preserve the credit of our Government, as will necessarily encourage among us the manufactures that we most need. And still more happily for us, the conduct of foreign governments towards us has put us under no obligations to any of them to arrange our revenue duties otherwise than we shall see to be best for ourselves. We can never be a great or a prosperous people until we change our policy, and combine with agriculture both manufactures and commerce. Entire freedom of trade would be the soundest policy, if the world would only promise to keep at peace forever. The principles of unrestricted commerce are abstractly true, but they cannot be put into practice without peril, so long as nation will make war against nation, and people will rise up against people. Under the American system of the old Government, which we all so bitterly oppossed, our suffering did not arise so much from duties considered abstractly in themselves, as from the fact that they operated almost entirely against the export of our great staples, while the money collected from them was almost all spent elsewhere. Of the money expended from the period of the adoption of the Federal Constitution until 1828, for all legitimate purposes under the Constitution, such as light-houses, fortifications, &c., fifty-eight millions were expended north of the Potomac, and but eight millions south of it. Such a condition of things could never occur under our new Confederacy, because our pursuits are similar, our population homogeneous, and our interests inseparably united. This is another morsel of meat from the mouth of the eater.

Until within a year after our war began, many of our own people, and almost all the nations outside of us, considered the institution of slavery as resting upon a very insecure basis. They almost universally believed that domestic insurrection would accompany foreign war, and that we should find our slaves rising “en masse,” and distracting all our efforts. Those who had studied this question most thoroughly, and looked at it in the light of philosophy, and especially of the Scriptures, did not fall into this error, and were satisfied from the beginning that the institution would come out of the war stronger than it went into it. Two years of the war have rid every one of any evil anticipations upon this head, and have satisfied the United States government that if these people are to change their condition, it must be changed for them by external force. And while this quiescence on the part of our servants vindicates us from the charges of cruelty and barbarity which have been so industriously circulated against us, it is also teaching us that we can, hereafter, with entire safety, and with most excellent results to ourselves, introduce them gradually to a higher moral and religious life. They know all that is going on. They are well informed about the proceedings of our enemies, and about their pretended philanthropy, and yet what advantage have they taken of it? When were they ever more quiet, more civil, more useful, more contented than they now are? Ignorance is really our worst enemy amongst them, and I sincerely hope that when this war is over, we shall, in token of their fidelity and good will, render their domestic relations more permanent, and consult more closely their feelings and affections, and thus extract sweetness from the strong mouth of this indiscriminate eater.

Before this war came upon us, the South almost worshipped personal bravery and physical courage. They were considered as the requisite qualities of every gentleman, and whosoever did not possess them, was pitied and despised, even while he was tolerated. No proper distinction was made between the courage of mere temperament and the moral courage of high principle. The duel was set up as the test of a man’s pretension to this quality. And this arose, partly from the natural spirit of our race, but was, likewise, a remnant of feudal usages, which are certainly out of place in our days. But this war is teaching us what an universal quality personal courage is, and how few men there are who are afraid of death upon the battle-field. How many tens of thousands of soldiers are there who, without any stimulus, save the sense of duty and the impulse of patriotism, march fearlessly up to the cannon’s mouth, literally sport with wounds and death, and stand upon the outermost verge of peril, and their check never blanches, and their step never falters. And is this physical courage, which is so valuable, yet so common, to be estimated above that moral courage, which is so rare–that courage which will not follow a multitude to do evil–which will breast the world in arms for principle–which will restrain the madness of the people at every sacrifice of place, of property, and of life? What we have needed in our civil affairs in the past has been this moral courage, and now we are learning in this war how much more rare a quality it is than mere personal bravery–such courage as made our gallant Johnson–Sydney in name and Sydney in nature–bear and suffer more than martyrdom, and then lay down in quiet dignity his valued life, that his country’s weakness might not be exposed–such courage as led our own heroic Tatnall to disappoint a nation’s hopes, and burn his ship rather than sacrifice his brave and trustful men to a selfish and bubble reputation for daring–such courage as has qualified our peerless President to face all calumny, rather than deviate one hair’s breadth from his own clear perception of his country’s good. It requires brave men to do these things. No common man can do them. And the longer the war lasts, the more will it develope such characteristics, and moral courage will rise in value, and mere physical courage–that which resolves bravery into brawling and duelling and private rencontres–will sink into merited insignificance. No people is more brave than the people which can boast of Nelson and Collingwood, of Hill and Wellington, and yet they find nobler employment for their courage than in wasting it upon the field of private revenge. And if we learn this truth, we shall indeed gain another morsel of delicious sweetness from the grasp of the strong.

These are some of the blessings which God is permitting us to take hold of, even in the midst of cruel war; and meanwhile he has not left us without great comfort. In the last ten months, He has granted us an almost uninterrupted series of victories, as if to give us heart and endurance for the conflict which He sees it best for us that we should continue to wage. Disappointed, as we have been, in our hopes of peace, the Father, who is disciplining us, has not given us over to despair. Peace, with its soft eye and its radiant wing, has not come to us, but victory has! Victory, under circumstances most glorious and unexpected–not only on the land, but upon the sea. His angel has planted one foot on the earth and the other on the ocean, and with his sword of vengeance has smitten this insulting and vain-glorious nation. And what a noble spirit has He infused into the heart of our Confederacy! How it has warmed anew into fervor Virginia, that old mother of heroes and of statesmen! How grandly she breasts the storm! Under the shadow of the Federal Government she seemed to be sinking into the slumber of death, as one dies under the shade of the poisonous Upas tree. But at the war-cry of her children, “Sic semper Tyrannis,” how her rich blood has rushed back upon her heart, and startled her into life! The sound of freedom’s cry has disenchanted her, and she has sprung full armed into the arena. Her noble sons have gathered around her from her hills and from her valleys, from all her fields of historic fame, from the blue waters of the Chesapeake to the dark rushing torrent of the Kanawha–sons worthy of such a mother. All her old energy has come back to her. All her power of self-denial and self-sacrifice has revived within her. Proud, fearless, indomitable, she looks into the very eye of tyranny, and makes it quail before her majesty of right and truth! The mother of States, she bares her bosom to receive upon it the strokes which are aimed at her children. Hurling defiance in the teeth of her oppressors, she prepares herself to conquer or to die. She hopes, she prays, she struggles for victory, but knowing that everything is in the hands of God, she presses on, uttering the noble words of DeRanville–“If the genius of evil is to prove triumphant, if legitimate government is again to fall, let it at least fall with honor; shame alone has no future.”