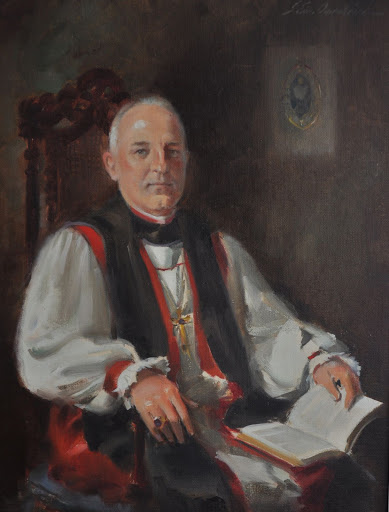

The Diocese elected a liturgist, ecumenist, and the son of a bishop to become the ninth Bishop of Georgia. Henry I. Louttit, Jr. was born in West Palm Beach, Florida in 1938, to the last bishop of the Diocese of South Florida before it was divided into three new dioceses. He was a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of the University of the South who married Jayne Arledge Northway in 1962. Louttit was ordained a deacon in 1963 on graduation from the Virginia Theological Seminary and a priest in 1964. He served first as the Vicar of Trinity Church in Statesboro, then as the rector of Christ Church in Valdosta where he served from 1967 until his election to the episcopacy in 1995. Louttit became the 9th Bishop of Georgia on January 21, 1995.

In his first address as bishop to Diocesan Convention, Bishop Louttit stated he believed the ministry of the bishop to be: an encourager, friend, and prayer supporter; the link between congregations in our diocese, throughout the world, and back through time to the apostles; the chief administrator, planner, and visioner; trouble-shooter, and reconciler; the sharer of family stories, like the grandfather of the family; an icon model of Christian service.

In his first address as bishop to Diocesan Convention, Bishop Louttit stated he believed the ministry of the bishop to be: an encourager, friend, and prayer supporter; the link between congregations in our diocese, throughout the world, and back through time to the apostles; the chief administrator, planner, and visioner; trouble-shooter, and reconciler; the sharer of family stories, like the grandfather of the family; an icon model of Christian service.

Long involved in liturgical renewal of the Episcopal Church, the bishop also had served a term as President of the Georgia Christian Council. He attended the Lambeth Conferences of 1998 and 2008 in Canterbury, England.

Bishop Louttit’s convention addresses focused on evangelism and church growth, conveying a firm concept of the ministry of “all the baptized.” Bishop Louttit promoted congregational development and fostered church planting. In Evans County, Holy Comforter was established from Saint Paul’s, Augusta; King of Peace was established in Kingsland, and St. Luke’s started in Rincon. A mission congregation, Our Savior, met for a time in the Chapel at Honey Creek. That mission and another, St. Stephen’s in Lee County, eventually closed.

In order that congregations which could not support a full-time priest would have the Eucharist every Sunday, Bishop Louttit initiated the training and formation of persons locally for ordination as bi-vocational priests, without seminary degree. 45 priests since have been raised up for ministry, formed in a variety of ways other than three years of residential seminary. Those priests have served faithfully in parishes and in significant leadership roles in the Diocese. The number of deacons also increased greatly in the diocese during his episcopate.

In order that congregations which could not support a full-time priest would have the Eucharist every Sunday, Bishop Louttit initiated the training and formation of persons locally for ordination as bi-vocational priests, without seminary degree. 45 priests since have been raised up for ministry, formed in a variety of ways other than three years of residential seminary. Those priests have served faithfully in parishes and in significant leadership roles in the Diocese. The number of deacons also increased greatly in the diocese during his episcopate.

In 2001 he and the Companion Diocese Committee recommended establishment of a Companion Diocese relationship with the Diocese of the Dominican Republic, the third such relationship for the Diocese of Georgia, Guiana and Belize being the previous two.

A major concern for the diocese, during Bishop Louttit’s episcopacy was the division that occurred in Christ Church in Savannah after the congregation voted in 2007 to separate from the Episcopal Church while continuing to possess the historic building on Johnson Square. Bishop Louttit assisted parishioners in founding a continuing Christ Church congregation to meet on Sunday evenings at the Church of St. Michael and All Angels. The property matter would be decided by the Georgia Supreme Court in favor of the Diocese during Bishop Scott Benhase’s episcopacy (2010-2020). On December 18, 2011, Christ Church Episcopal moved back to the Johnson Square property with a grateful and joyful liturgy during which Bishop Louttit celebrated the Eucharist. Bishop Louttit had kept the diocese largely united during a period of controversy.

A major concern for the diocese, during Bishop Louttit’s episcopacy was the division that occurred in Christ Church in Savannah after the congregation voted in 2007 to separate from the Episcopal Church while continuing to possess the historic building on Johnson Square. Bishop Louttit assisted parishioners in founding a continuing Christ Church congregation to meet on Sunday evenings at the Church of St. Michael and All Angels. The property matter would be decided by the Georgia Supreme Court in favor of the Diocese during Bishop Scott Benhase’s episcopacy (2010-2020). On December 18, 2011, Christ Church Episcopal moved back to the Johnson Square property with a grateful and joyful liturgy during which Bishop Louttit celebrated the Eucharist. Bishop Louttit had kept the diocese largely united during a period of controversy.

Pictured: (top) Bishop Louttit at his consecration in Roman Catholic Cathedral, St. John the Baptist in Savannah, (upper middle) Bishop Henry and Jan Louttit, (lower middle) Julias Ariail’s photo of Bishop Louttit preaching to the 2009 electing convention for his successor, and (bottom) as we close out this series on our history, the 9th, 10th, and 8th Bishops of the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia, the Rt. Revs. Henry Louttit, Scott Benhase, and Harry Shipps, sharing a laugh before the convention Eucharist in 2016 in a photo taken by Canon to the Ordinary who would become the 11th Bishop, Frank Logue.

As we approach the bicentennial of our founding, From the Field has shared the story of the Diocese of Georgia in 42 articles. When possible, the articles relied on quotations from contemporary accounts or the person’s own words to assist in sharing history the way those who lived it told their story. Though more than 22-thousand words in length, this series is far from a complete history. Yet we have seen many of the people and events that have shaped our Diocese. Along the way, the abiding characteristics of our Diocese, resilience and adaptability, have been revealed together with the ways we have changed, in seeing the image of God in all people.

As we approach the bicentennial of our founding, From the Field has shared the story of the Diocese of Georgia in 42 articles. When possible, the articles relied on quotations from contemporary accounts or the person’s own words to assist in sharing history the way those who lived it told their story. Though more than 22-thousand words in length, this series is far from a complete history. Yet we have seen many of the people and events that have shaped our Diocese. Along the way, the abiding characteristics of our Diocese, resilience and adaptability, have been revealed together with the ways we have changed, in seeing the image of God in all people. The series ends with next week’s article on the ninth Bishop of Georgia, the Rt. Rev. Henry I. Louttit, Jr. The story of the Diocese from 2010 onward will be written in time. We end there as perspective assists in considering history. One notable example of how this is true is that the book

The series ends with next week’s article on the ninth Bishop of Georgia, the Rt. Rev. Henry I. Louttit, Jr. The story of the Diocese from 2010 onward will be written in time. We end there as perspective assists in considering history. One notable example of how this is true is that the book  A Christianity Today article described the transition leading to that moment: “In the midst of rethinking evangelical worship, White became seized with what he calls an ‘ecumenical spirit.’ He studied Roman Catholicism as well as Anglicanism, Lutheranism, and other liturgical traditions. A friend gave him a copy of the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer, which White began using in his private devotions. Most important, he attended a liturgical church and felt a spiritual quickening. ‘I experienced God there,’ White says, his voice still registering astonishment several years after the event. ‘That wasn’t supposed to happen. It shocked me.’”

A Christianity Today article described the transition leading to that moment: “In the midst of rethinking evangelical worship, White became seized with what he calls an ‘ecumenical spirit.’ He studied Roman Catholicism as well as Anglicanism, Lutheranism, and other liturgical traditions. A friend gave him a copy of the Episcopal Book of Common Prayer, which White began using in his private devotions. Most important, he attended a liturgical church and felt a spiritual quickening. ‘I experienced God there,’ White says, his voice still registering astonishment several years after the event. ‘That wasn’t supposed to happen. It shocked me.’” Bishop Shipps encouraged the move and the canonical process was begun. Shipps charged two nearby priests, the Rev. Jacoba Hurst of St. Anne’s in Tifton and the Rev. Henry Louttit of Christ Church in Valdosta, with preparing the pastor for ordination to the diaconate and priesthood, and the congregation for confirmation. Hurst described going before the commission on ministry to a Christianity Today reporter saying that feared he had ushered White into the seat of the scornful. “Some of these guys are rather hostile, dour clerics who don’t suffer fools gladly,” Hurst recalled. “They were reserved and cautious at first,” he said; but then something extraordinary happened: “There was the presence of God in that room.” He continued, “I couldn’t speak. It was like some kind of revival” noting several committee members were weeping.

Bishop Shipps encouraged the move and the canonical process was begun. Shipps charged two nearby priests, the Rev. Jacoba Hurst of St. Anne’s in Tifton and the Rev. Henry Louttit of Christ Church in Valdosta, with preparing the pastor for ordination to the diaconate and priesthood, and the congregation for confirmation. Hurst described going before the commission on ministry to a Christianity Today reporter saying that feared he had ushered White into the seat of the scornful. “Some of these guys are rather hostile, dour clerics who don’t suffer fools gladly,” Hurst recalled. “They were reserved and cautious at first,” he said; but then something extraordinary happened: “There was the presence of God in that room.” He continued, “I couldn’t speak. It was like some kind of revival” noting several committee members were weeping. Bishop Paul Reeves was clear in his opposition to women’s ordination, “this action needs to be seen as but one manifestation of what appears to be a widespread breakdown of sound doctrine and discipline in the Church.” During this time several clergy of the diocese, troubled by the ordination of women, accepted the Pastoral Provision offered by Pope John Paul II in 1980, which allowed for married Episcopal priests to be re-ordained Roman Catholic priests. Three Georgia diocesan priests accepted the offer. Bishop Reeves was supportive of their decision.

Bishop Paul Reeves was clear in his opposition to women’s ordination, “this action needs to be seen as but one manifestation of what appears to be a widespread breakdown of sound doctrine and discipline in the Church.” During this time several clergy of the diocese, troubled by the ordination of women, accepted the Pastoral Provision offered by Pope John Paul II in 1980, which allowed for married Episcopal priests to be re-ordained Roman Catholic priests. Three Georgia diocesan priests accepted the offer. Bishop Reeves was supportive of their decision.  Early dissent to the ordination of women organized into a group called The Traditionalist Clergy of the Diocese of Georgia. Approximately a dozen diocesan priests attended meetings in Dublin, supported by Bishop Paul Reeves, who came from his retirement home in North Carolina. Bishop Shipps attended several gatherings to explain his positions. The ordination issue led to a split in the congregation of St. John’s in Moultrie, resulting in formation of the congregation of St. Margaret of Scotland.

Early dissent to the ordination of women organized into a group called The Traditionalist Clergy of the Diocese of Georgia. Approximately a dozen diocesan priests attended meetings in Dublin, supported by Bishop Paul Reeves, who came from his retirement home in North Carolina. Bishop Shipps attended several gatherings to explain his positions. The ordination issue led to a split in the congregation of St. John’s in Moultrie, resulting in formation of the congregation of St. Margaret of Scotland.  Pictured: (top) a newspaper article on the Rev. Sonia Sullivan Clifton’s ordination, (middle) Bishop Shipps is pictured above with the clergy of the Diocese at a diocesan convention, and (bottom) Bishop Logue with clergy at the 2022 diocesan convention.

Note: This article was edited from Bishop Shipps’ reflections on his episcopacy with an update added to the end of the article above.

Pictured: (top) a newspaper article on the Rev. Sonia Sullivan Clifton’s ordination, (middle) Bishop Shipps is pictured above with the clergy of the Diocese at a diocesan convention, and (bottom) Bishop Logue with clergy at the 2022 diocesan convention.

Note: This article was edited from Bishop Shipps’ reflections on his episcopacy with an update added to the end of the article above.

He was consecrated bishop at Christ Church in Savannah on the Feast of the Epiphany in 1984. Bishop Shipps served as coadjutor to Bishop Reeves. Early in his episcopate, Bishop Shipps called the Rev. J. Robert Carter, Vicar of Trinity in Statesboro to serve as Canon to the Ordinary.

He was consecrated bishop at Christ Church in Savannah on the Feast of the Epiphany in 1984. Bishop Shipps served as coadjutor to Bishop Reeves. Early in his episcopate, Bishop Shipps called the Rev. J. Robert Carter, Vicar of Trinity in Statesboro to serve as Canon to the Ordinary. Bishop Shipps and The Most Rev. Raymond W. Lessard, Roman Catholic Bishop of Savannah, held several joint clergy conferences with noted speakers from both Churches. This led to a Covenant between the two dioceses calling for a number of programs and responsibilities on the part of each.

Bishop Shipps and The Most Rev. Raymond W. Lessard, Roman Catholic Bishop of Savannah, held several joint clergy conferences with noted speakers from both Churches. This led to a Covenant between the two dioceses calling for a number of programs and responsibilities on the part of each.  Canonically resident in the Diocese of South Florida at the time of his election, he was consecrated bishop coadjutor to serve alongside Bishop Albert Rhett Stuart in Christ Church, Savannah, on September 30, 1969. Bishop Reeves became diocesan bishop on Stuart’s retirement in 1972. In his first Convention address he stressed the centrality of Holy Eucharist as the norm for Sunday worship and the obligation of faithful, regular attendance at church.

Canonically resident in the Diocese of South Florida at the time of his election, he was consecrated bishop coadjutor to serve alongside Bishop Albert Rhett Stuart in Christ Church, Savannah, on September 30, 1969. Bishop Reeves became diocesan bishop on Stuart’s retirement in 1972. In his first Convention address he stressed the centrality of Holy Eucharist as the norm for Sunday worship and the obligation of faithful, regular attendance at church.  To name Bishop Reeves solely as a conservative in a theologically-divided church fails to capture the gifts he brought to his call. Bishop Harry Shipps wrote that, “Reeves was a conservative gentleman with a dry sense of humor. He held a high view of the Church and our individual and corporate responsibility to it as stewards.”

To name Bishop Reeves solely as a conservative in a theologically-divided church fails to capture the gifts he brought to his call. Bishop Harry Shipps wrote that, “Reeves was a conservative gentleman with a dry sense of humor. He held a high view of the Church and our individual and corporate responsibility to it as stewards.” To support the evangelistic effort, the diocese used roadside billboards, bumper stickers, posters, stacks of calling cards in motels, signs of every description, radio, TV, and newspaper advertising, and a diocesan-wide telephone campaign.

To support the evangelistic effort, the diocese used roadside billboards, bumper stickers, posters, stacks of calling cards in motels, signs of every description, radio, TV, and newspaper advertising, and a diocesan-wide telephone campaign. This evangelistic effort was the result of meticulous planning under one General Crusade Committee five subcommittees served, each dealing with a specific area: spiritual preparation, services, finance, promotion and publicity, and follow-up. Each of these had a counterpart in the twelve areas which were designated as preaching stations.

This evangelistic effort was the result of meticulous planning under one General Crusade Committee five subcommittees served, each dealing with a specific area: spiritual preparation, services, finance, promotion and publicity, and follow-up. Each of these had a counterpart in the twelve areas which were designated as preaching stations. Bishop Harry Shipps held another Bishops’ Crusade in 1986. Twelve bishops from across the country were once again commissioned, this time by Presiding Bishop John M. Allin in a service at Christ Church in Savannah. They were sent to twelve parishes around the diocese for a three day preaching mission and interaction with parishioners. In January of 2018, Bishop Scott Benhase hosted a revival at Honey Creek. Presiding Bishop Michael Curry brought evangelical fervor to an immense revival tent on the grounds of the retreat center.

Bishop Harry Shipps held another Bishops’ Crusade in 1986. Twelve bishops from across the country were once again commissioned, this time by Presiding Bishop John M. Allin in a service at Christ Church in Savannah. They were sent to twelve parishes around the diocese for a three day preaching mission and interaction with parishioners. In January of 2018, Bishop Scott Benhase hosted a revival at Honey Creek. Presiding Bishop Michael Curry brought evangelical fervor to an immense revival tent on the grounds of the retreat center.  In 1955 a young architect, Blake Ellis an Episcopalian fresh out of Georgia Tech, was approached by Bishop Albert Stuart to layout a master plan and design the buildings for a new camp and conference center in Camden County. Many names of buildings from the former Camp Reese were honored at Honey Creek. Ellis, a long-term communicant at Christ Church in Valdosta, designed the Chapel of Our Savior, three dormitories, a dining hall, and two cottages on the 100-acre maritime forest along the tidal creek. These buildings and a pool were completed in time for springtime retreats for adults and the first summer camp session in 1960. The Department of Christian Education of the Diocese planned programs which were participated in by 622 men, women, boys and girls. It was an invaluable experience in Christian living and Christian education. That the first year of use of the new Center proved to be such a smooth operation with such fine results was due to the careful planning and hard work of the teaching staffs and permanent staff, and above all to the devotion of Mr. and Mrs. Sherman Hammatt, the first resident Custodians. Bishop Stuart also facilitated a widely acclaimed free annual camping program for 400 underprivileged children at Honey Creek. Credit for the success of the program was widely given to the organizer, Commander Robert Clinton of St. John’s in Moultrie.

In 1955 a young architect, Blake Ellis an Episcopalian fresh out of Georgia Tech, was approached by Bishop Albert Stuart to layout a master plan and design the buildings for a new camp and conference center in Camden County. Many names of buildings from the former Camp Reese were honored at Honey Creek. Ellis, a long-term communicant at Christ Church in Valdosta, designed the Chapel of Our Savior, three dormitories, a dining hall, and two cottages on the 100-acre maritime forest along the tidal creek. These buildings and a pool were completed in time for springtime retreats for adults and the first summer camp session in 1960. The Department of Christian Education of the Diocese planned programs which were participated in by 622 men, women, boys and girls. It was an invaluable experience in Christian living and Christian education. That the first year of use of the new Center proved to be such a smooth operation with such fine results was due to the careful planning and hard work of the teaching staffs and permanent staff, and above all to the devotion of Mr. and Mrs. Sherman Hammatt, the first resident Custodians. Bishop Stuart also facilitated a widely acclaimed free annual camping program for 400 underprivileged children at Honey Creek. Credit for the success of the program was widely given to the organizer, Commander Robert Clinton of St. John’s in Moultrie. In the 1970’s, Reese Dining Hall and kitchen were expanded to allow for more indoor gathering space. The 1970’s also brought a new and larger meeting space named Stuart Hall for the Bishop. In the early days of the 1990’s, under the leadership of the Rev. Charles and Dot Hay, a successful environmental education program began, and a new campus office was built, along with twenty additional lodge rooms.

In the 1970’s, Reese Dining Hall and kitchen were expanded to allow for more indoor gathering space. The 1970’s also brought a new and larger meeting space named Stuart Hall for the Bishop. In the early days of the 1990’s, under the leadership of the Rev. Charles and Dot Hay, a successful environmental education program began, and a new campus office was built, along with twenty additional lodge rooms. Bishop Stuart and his family lived in the episcopal residence on Victory Drive and Reynolds Street in Savannah. The diocesan office at that time was in the basement of Christ Church in Savannah; the sole full time employee Olwyn Morgan, a native of Wales. Bishop Stuart moved the offices to 611 East Bay Street, which allowed for additional staff and a chapel. The bishop’s wife, Isabella, died in an automobile accident in South Carolina enroute to their vacation cottage. She was, of course, much mourned by the Diocese, as well as by Bishop Stuart and his family.

Bishop Stuart and his family lived in the episcopal residence on Victory Drive and Reynolds Street in Savannah. The diocesan office at that time was in the basement of Christ Church in Savannah; the sole full time employee Olwyn Morgan, a native of Wales. Bishop Stuart moved the offices to 611 East Bay Street, which allowed for additional staff and a chapel. The bishop’s wife, Isabella, died in an automobile accident in South Carolina enroute to their vacation cottage. She was, of course, much mourned by the Diocese, as well as by Bishop Stuart and his family. Bishop Stuart always dressed in black vest and white shirt with French cuffs. Bishop Harry Shipps wrote of Stuart that he was, “The epitome of a Southern gentleman, he had impeccable credentials, strong leadership skills, and innate wisdom, all of which served him well as the storm clouds of racial unrest appeared over the South.”

Bishop Stuart always dressed in black vest and white shirt with French cuffs. Bishop Harry Shipps wrote of Stuart that he was, “The epitome of a Southern gentleman, he had impeccable credentials, strong leadership skills, and innate wisdom, all of which served him well as the storm clouds of racial unrest appeared over the South.” In 1911, Bishop Reese reported to the all white convention of the Council for black Episcopalians, “every possible opportunity should be given this Council and responsibility laid upon it for the direction of the work among their own people.”

In 1911, Bishop Reese reported to the all white convention of the Council for black Episcopalians, “every possible opportunity should be given this Council and responsibility laid upon it for the direction of the work among their own people.” Diocesan conventions continued to be segregated as black Episcopalians met in a separate Council presided over by the Bishop of Georgia. In 1946, the Federal Council of Churches condemned discrimination as Mainline Protestant churches began to move towards the goal of a “desegregated church in a desegregated society.” The Federal Council of Churches named discrimination as a “violation of the gospel of love and human brotherhood.”

Diocesan conventions continued to be segregated as black Episcopalians met in a separate Council presided over by the Bishop of Georgia. In 1946, the Federal Council of Churches condemned discrimination as Mainline Protestant churches began to move towards the goal of a “desegregated church in a desegregated society.” The Federal Council of Churches named discrimination as a “violation of the gospel of love and human brotherhood.” The convention approved a new slate with Dr. Lawrence back on the ballot with the bishops considered in the first special convention brought back for consideration: Missionary Bishop William P. Remington of Oregon, Missionary Bishop Elmer N. Schmuck of Wyoming, and Missionary Bishop Middleton Stuart Barnwell of Idaho. Bishop Barnwell’s name led the votes in each order without getting a majority. On the ninth ballot, the convention elected Bishop Barnwell as Bishop Coadjutor.

The convention approved a new slate with Dr. Lawrence back on the ballot with the bishops considered in the first special convention brought back for consideration: Missionary Bishop William P. Remington of Oregon, Missionary Bishop Elmer N. Schmuck of Wyoming, and Missionary Bishop Middleton Stuart Barnwell of Idaho. Bishop Barnwell’s name led the votes in each order without getting a majority. On the ninth ballot, the convention elected Bishop Barnwell as Bishop Coadjutor. Sarah “Sada” Barnwell Elliott (1848-1928) was born at the Montpelier Institute, which her father, Bishop Stephen Elliott founded near Forsyth, Georgia. Elliott was a strong proponent of education for women. Bishop Elliott died in 1866, when Sada was 18. She moved to Sewanee with her mother in 1871 and other than attending classes at Johns Hopkins University in 1886 and living in New York City from 1895 to 1904, she was on the Mountain the remainder of her life.

Sarah “Sada” Barnwell Elliott (1848-1928) was born at the Montpelier Institute, which her father, Bishop Stephen Elliott founded near Forsyth, Georgia. Elliott was a strong proponent of education for women. Bishop Elliott died in 1866, when Sada was 18. She moved to Sewanee with her mother in 1871 and other than attending classes at Johns Hopkins University in 1886 and living in New York City from 1895 to 1904, she was on the Mountain the remainder of her life. Nellie Rathbone Bright (1898-1977) was born in Savannah to the Rev. Richard and Nellie Bright. Her father was the Rector of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Savannah. Her mother, Nellie, was educated in Europe as a teacher. The Bright’s valued education and established the first private kindergarten and primary school for blacks in Georgia. When their daughter, also named Nellie, was 12, the family moved to Philadelphia as part of the Great Migration. After graduation from the University of Pennsylvania in 1923 with a Bachelors in English, Bright taught in Philadelphia public schools. She served as a principal from 1935 until her 1952 retirement. During the 1920s she was part of a literary group known as the Black Opals. In 1927–1928, She co-edited Black Opals, together with Arthur Fauset. The literary magazine, published in Philadelphia, was part of the larger influence of the Harlem Renaissance.

Nellie Rathbone Bright (1898-1977) was born in Savannah to the Rev. Richard and Nellie Bright. Her father was the Rector of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Savannah. Her mother, Nellie, was educated in Europe as a teacher. The Bright’s valued education and established the first private kindergarten and primary school for blacks in Georgia. When their daughter, also named Nellie, was 12, the family moved to Philadelphia as part of the Great Migration. After graduation from the University of Pennsylvania in 1923 with a Bachelors in English, Bright taught in Philadelphia public schools. She served as a principal from 1935 until her 1952 retirement. During the 1920s she was part of a literary group known as the Black Opals. In 1927–1928, She co-edited Black Opals, together with Arthur Fauset. The literary magazine, published in Philadelphia, was part of the larger influence of the Harlem Renaissance. No one in Sumter County had encountered a minister like the Rev. Dr. James Bolan Lawrence (1878-1947)—“He smoked, he drank, he liked good stories.” He attended country club dances and made headlines for preaching a sermon in favor of golf on Sunday.

No one in Sumter County had encountered a minister like the Rev. Dr. James Bolan Lawrence (1878-1947)—“He smoked, he drank, he liked good stories.” He attended country club dances and made headlines for preaching a sermon in favor of golf on Sunday. Davenport recalls how though he was often ignored, laughed at and publicly made fun of, Dr. Lawrence persevered. He tirelessly worked to live out the Gospel. He carried the sick to hospitals, helped rehabilitate alcoholics, assisted boys and girls to get an education while teaching others himself. Little by little, she wrote, this county seat town observed the odd man with his collar on backwards helping people “high and low, rich and poor, young and old, good and bad.” He was versed in Greek, Latin and French, but he was never heard talking down to anyone. Too old to fight in World War I, he went into the YMCA and served near the front just the same. He returned from the war to take back up his steadfast example of trying to follow Christ.

Davenport recalls how though he was often ignored, laughed at and publicly made fun of, Dr. Lawrence persevered. He tirelessly worked to live out the Gospel. He carried the sick to hospitals, helped rehabilitate alcoholics, assisted boys and girls to get an education while teaching others himself. Little by little, she wrote, this county seat town observed the odd man with his collar on backwards helping people “high and low, rich and poor, young and old, good and bad.” He was versed in Greek, Latin and French, but he was never heard talking down to anyone. Too old to fight in World War I, he went into the YMCA and served near the front just the same. He returned from the war to take back up his steadfast example of trying to follow Christ. In 1947 when Mr. Lawrence retired from active service, Bishop Barnwell commented on the Archdeacon’s forty-three years of faithful duty: “So far as my knowledge of the record goes, this is the longest period of service rendered by any man in the history of the Diocese.” He added, “Dr. Lawrence is still a missionary.”

In 1947 when Mr. Lawrence retired from active service, Bishop Barnwell commented on the Archdeacon’s forty-three years of faithful duty: “So far as my knowledge of the record goes, this is the longest period of service rendered by any man in the history of the Diocese.” He added, “Dr. Lawrence is still a missionary.” Eleven additional lots were added and buildings given in subsequent years. St. John’s Church in Savannah built Jonnard Cottage in 1933. The next year, Christ Church in Savannah built Wright Cottage in honor of their Rector, the Rev. David Cady Wright. St. Paul’s and Good Shepherd in Augusta added the Augusta Cottage in 1936. Funded from various gifts in 1938, Aiken Cottage was named in honor of Frank Aiken of Brunswick. Also in 1938, the Young People’s Service Group built Alexander Cottage in honor of Deaconess Anna Alexander who worked at the camp in the summer to raise money to support the school in Pennick. Alexander Cottage was described as a servants’ house for the camp.

Eleven additional lots were added and buildings given in subsequent years. St. John’s Church in Savannah built Jonnard Cottage in 1933. The next year, Christ Church in Savannah built Wright Cottage in honor of their Rector, the Rev. David Cady Wright. St. Paul’s and Good Shepherd in Augusta added the Augusta Cottage in 1936. Funded from various gifts in 1938, Aiken Cottage was named in honor of Frank Aiken of Brunswick. Also in 1938, the Young People’s Service Group built Alexander Cottage in honor of Deaconess Anna Alexander who worked at the camp in the summer to raise money to support the school in Pennick. Alexander Cottage was described as a servants’ house for the camp. During the post World War II years, the Diocese added two new buildings, a chapel and a recreational hall, the latter a memorial to Lt. Carl Schuessler, a U. S. Marine who lost his life in the Pacific after serving seven years on the staff of the camp. A tabby outdoor altar under the branches of a majestic live oak served as a beloved outdoor chapel, named Barnwell Chapel, for Bishop Reese’s successor, the Rt. Rev. Middleton Stuart Barnwell.

During the post World War II years, the Diocese added two new buildings, a chapel and a recreational hall, the latter a memorial to Lt. Carl Schuessler, a U. S. Marine who lost his life in the Pacific after serving seven years on the staff of the camp. A tabby outdoor altar under the branches of a majestic live oak served as a beloved outdoor chapel, named Barnwell Chapel, for Bishop Reese’s successor, the Rt. Rev. Middleton Stuart Barnwell. This system assisted in building churches. For example, an auction for pews in Columbus raised a revenue of $3,369 a year in 1835, making the construction possible (this is $105,855 in 2022 dollars). Yet the system was not never perfect. The Panic of 1837 was devastating to the economy. By October, 1839, creditors filed suit against the church for failing to make its payments as pew rents fell to less than $1,000 a year in 1839-1840.

This system assisted in building churches. For example, an auction for pews in Columbus raised a revenue of $3,369 a year in 1835, making the construction possible (this is $105,855 in 2022 dollars). Yet the system was not never perfect. The Panic of 1837 was devastating to the economy. By October, 1839, creditors filed suit against the church for failing to make its payments as pew rents fell to less than $1,000 a year in 1839-1840. Bishop Stephen Elliott had mentioned the obstacle pew rents presented in some of his Bishop Addresses. For example, in 1854 he said, “To be pointed at as the church of the rich and the refined and the fashionable, when Christ had given it as one of the marks of his mission, that the gospel was preached unto the poor, was a condition under which she was not satisfied to rest.”

Bishop Stephen Elliott had mentioned the obstacle pew rents presented in some of his Bishop Addresses. For example, in 1854 he said, “To be pointed at as the church of the rich and the refined and the fashionable, when Christ had given it as one of the marks of his mission, that the gospel was preached unto the poor, was a condition under which she was not satisfied to rest.” He spoke to the faithful work underway by African American clergy, “Our colored clergy are, I believe, faithful, earnest men. Some of them are exceptional men among their people, men of character and devotion. They are laboring under great difficulties and with poor and inadequate support. They are making bricks with but little straw.”

He spoke to the faithful work underway by African American clergy, “Our colored clergy are, I believe, faithful, earnest men. Some of them are exceptional men among their people, men of character and devotion. They are laboring under great difficulties and with poor and inadequate support. They are making bricks with but little straw.” At this same time debate at the church-wide level focused on two competing plans for expanding work among African Americans. One plan would elect from black clergy some suffragan bishops who served under the bishop diocesan. The second plan would create missionary districts served by blacks bishops who did not report to a diocesan. The Diocese of Georgia preferred raising up a Bishop Suffragans as a report read, “We believe that there is a real necessity and a justifiable demand on the part of the negro Churchmen for authorized leaders of their own race if our Church is to command the allegiance of that Race.” Suffragans would not be given a vote in the House of Bishops or the right to become a diocesan bishop. The same report noted that this was the “only plan by which complete control on the part of the white Bishop of the Diocese can still be maintained.”

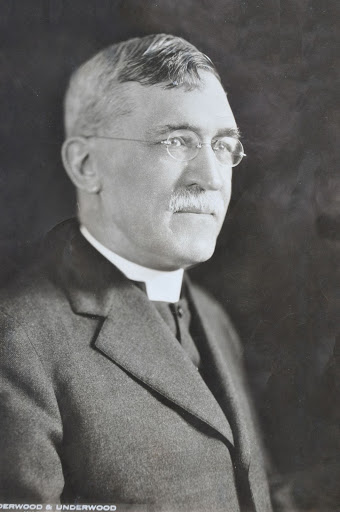

At this same time debate at the church-wide level focused on two competing plans for expanding work among African Americans. One plan would elect from black clergy some suffragan bishops who served under the bishop diocesan. The second plan would create missionary districts served by blacks bishops who did not report to a diocesan. The Diocese of Georgia preferred raising up a Bishop Suffragans as a report read, “We believe that there is a real necessity and a justifiable demand on the part of the negro Churchmen for authorized leaders of their own race if our Church is to command the allegiance of that Race.” Suffragans would not be given a vote in the House of Bishops or the right to become a diocesan bishop. The same report noted that this was the “only plan by which complete control on the part of the white Bishop of the Diocese can still be maintained.” Despite the challenges, there were seven nominees for bishop–two were clergy from within the diocese while five were serving elsewhere in the southeast. Frederick Focke Reese was among the three leading candidates on the first ballot and was elected by majority vote of both lay and clergy orders on the fourth ballot. Born in Baltimore, Maryland on October 23, 1854, Reese graduated from the University of Maryland and Berkeley Theological Seminary (at Yale University) before his ordination to the priesthood in 1877. He served as an Episcopal priest in Baltimore, then in Virginia. He was well known in the Diocese as he had served as the Rector of Christ Church in Macon, during which time he was the Secretary of the Convention of the Diocese of Georgia. At the time of his election, Reese was the Rector of Christ Church, Nashville. He was consecrated in Christ Church, Savannah on May 20, 1908. Almost immediately, poor health caused the newly elected bishop to take an extended leave of absence. He resumed ecclesiastical duties April 1, 1909.

Despite the challenges, there were seven nominees for bishop–two were clergy from within the diocese while five were serving elsewhere in the southeast. Frederick Focke Reese was among the three leading candidates on the first ballot and was elected by majority vote of both lay and clergy orders on the fourth ballot. Born in Baltimore, Maryland on October 23, 1854, Reese graduated from the University of Maryland and Berkeley Theological Seminary (at Yale University) before his ordination to the priesthood in 1877. He served as an Episcopal priest in Baltimore, then in Virginia. He was well known in the Diocese as he had served as the Rector of Christ Church in Macon, during which time he was the Secretary of the Convention of the Diocese of Georgia. At the time of his election, Reese was the Rector of Christ Church, Nashville. He was consecrated in Christ Church, Savannah on May 20, 1908. Almost immediately, poor health caused the newly elected bishop to take an extended leave of absence. He resumed ecclesiastical duties April 1, 1909. Bishop Nelson would tell the convention that the need for two diocesan bishops was largely one of authority, “Observation and experience have convinced me that no arrangement of agent, Archdeacon or Coadjutor will ever satisfy the demands among these people who are most amenable when brought into direct touch with the authoritative head of affairs, but do not heed an intermediary.”

Bishop Nelson would tell the convention that the need for two diocesan bishops was largely one of authority, “Observation and experience have convinced me that no arrangement of agent, Archdeacon or Coadjutor will ever satisfy the demands among these people who are most amenable when brought into direct touch with the authoritative head of affairs, but do not heed an intermediary.” Anna continued to teach in Darien. Each Sunday she made a round trip of forty miles by boat and foot. In 1897, however, Anna was accepted at St. Paul’s School [now College] in Virginia. She returned three years later to establish a school and revive the church. For the first year, Anna taught at home and supported herself by taking in sewing. Anna raised funds to buy the land and purchase lumber for the school.

Anna continued to teach in Darien. Each Sunday she made a round trip of forty miles by boat and foot. In 1897, however, Anna was accepted at St. Paul’s School [now College] in Virginia. She returned three years later to establish a school and revive the church. For the first year, Anna taught at home and supported herself by taking in sewing. Anna raised funds to buy the land and purchase lumber for the school. She would continue in ministry until 1945, finding support largely from philanthropists in the north as she received no assistance from her Diocese. She served her entire ministry as a deaconess in a segregated church as a separate meeting for black Episcopalians met apart from diocesan conventions from 1907-1947.

She would continue in ministry until 1945, finding support largely from philanthropists in the north as she received no assistance from her Diocese. She served her entire ministry as a deaconess in a segregated church as a separate meeting for black Episcopalians met apart from diocesan conventions from 1907-1947. The convention reconvened on November 11 with four priests of the Diocese of Georgia on the slate along with the rector of Christ Church in Detroit, Michigan, and the Rev. Cleland Kinloch Nelson, rector of the Church of the Nativity in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Nelson received majorities in both houses, with scattered votes for Johnson and the four Georgia clergy.

The convention reconvened on November 11 with four priests of the Diocese of Georgia on the slate along with the rector of Christ Church in Detroit, Michigan, and the Rev. Cleland Kinloch Nelson, rector of the Church of the Nativity in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Nelson received majorities in both houses, with scattered votes for Johnson and the four Georgia clergy. Missionary work resulted in sustained growth of the Episcopal Church in Georgia in the decades following the American Civil War. During Bishop John Beckwith’s 23 years as Bishop of Georgia, he averaged a little more than one new congregation every year as he added 22 congregations and five missions. Realizing that the state of Georgia was too big for one person to handle alone, Beckwith made administrative changes to enable the expansion. At the Diocesan Convention of 1870, a new canon was adopted which established four missionary districts. This relieved the Bishop of the sole responsibility for stimulating, establishing, and maintaining new missions.

Missionary work resulted in sustained growth of the Episcopal Church in Georgia in the decades following the American Civil War. During Bishop John Beckwith’s 23 years as Bishop of Georgia, he averaged a little more than one new congregation every year as he added 22 congregations and five missions. Realizing that the state of Georgia was too big for one person to handle alone, Beckwith made administrative changes to enable the expansion. At the Diocesan Convention of 1870, a new canon was adopted which established four missionary districts. This relieved the Bishop of the sole responsibility for stimulating, establishing, and maintaining new missions. This pattern of Episcopalians moving to town, beginning to meet on their own, and then asking for some diocesan assistance was common. Financing the missionary efforts became an ongoing problem. It was readily apparent that the parish clergy were too busy with parochial duties to give effective missionary service on a regular basis. The Diocese assigned and paid the compensation for a mission minister-in-charge for these stations. By 1880 the Diocese had established a Board of Missions with responsibility for the ambitious missionary operations. This group consisted of the Bishop, the four Deans, and four laymen who apportioned monies to “the feeble Parishes and Mission Stations.”

This pattern of Episcopalians moving to town, beginning to meet on their own, and then asking for some diocesan assistance was common. Financing the missionary efforts became an ongoing problem. It was readily apparent that the parish clergy were too busy with parochial duties to give effective missionary service on a regular basis. The Diocese assigned and paid the compensation for a mission minister-in-charge for these stations. By 1880 the Diocese had established a Board of Missions with responsibility for the ambitious missionary operations. This group consisted of the Bishop, the four Deans, and four laymen who apportioned monies to “the feeble Parishes and Mission Stations.” The young Dodge fell in love with his younger first cousin, Ellen Ada Phelps. Their marriage in 1880 created a scandal. Eventually, the family agreed to the match. The couple planned an ambitious 3-year trip around the world as their honeymoon journey. In India, Ellen contracted cholera and died. Devastated by her death, Anson had his wife embalmed and placed in a metal coffin inside an ebony casket. He had promised her on her death bed that he would not leave her side. True to his word, he remained by her casket in the hold of the ship for a long return journey. He buried her under the altar at Frederica on his return to the Georgia coast. In time, he remarried. His second wife, Anna Gould Dodge, gave birth to a son. Their son also died tragically when he fell from a carriage at the age of three.

The young Dodge fell in love with his younger first cousin, Ellen Ada Phelps. Their marriage in 1880 created a scandal. Eventually, the family agreed to the match. The couple planned an ambitious 3-year trip around the world as their honeymoon journey. In India, Ellen contracted cholera and died. Devastated by her death, Anson had his wife embalmed and placed in a metal coffin inside an ebony casket. He had promised her on her death bed that he would not leave her side. True to his word, he remained by her casket in the hold of the ship for a long return journey. He buried her under the altar at Frederica on his return to the Georgia coast. In time, he remarried. His second wife, Anna Gould Dodge, gave birth to a son. Their son also died tragically when he fell from a carriage at the age of three. Thus, he dedicated his new congregations to St. Ignatius, St. Cyprian, St. Ambrose, St. Perpetua, St. Athanasius, as well as to the Messiah, Transfiguration, and St. Andrew. He founded six chapels along the Satilla River. He worked as far inland as Waycross, founding the Church of St. Ambrose there.

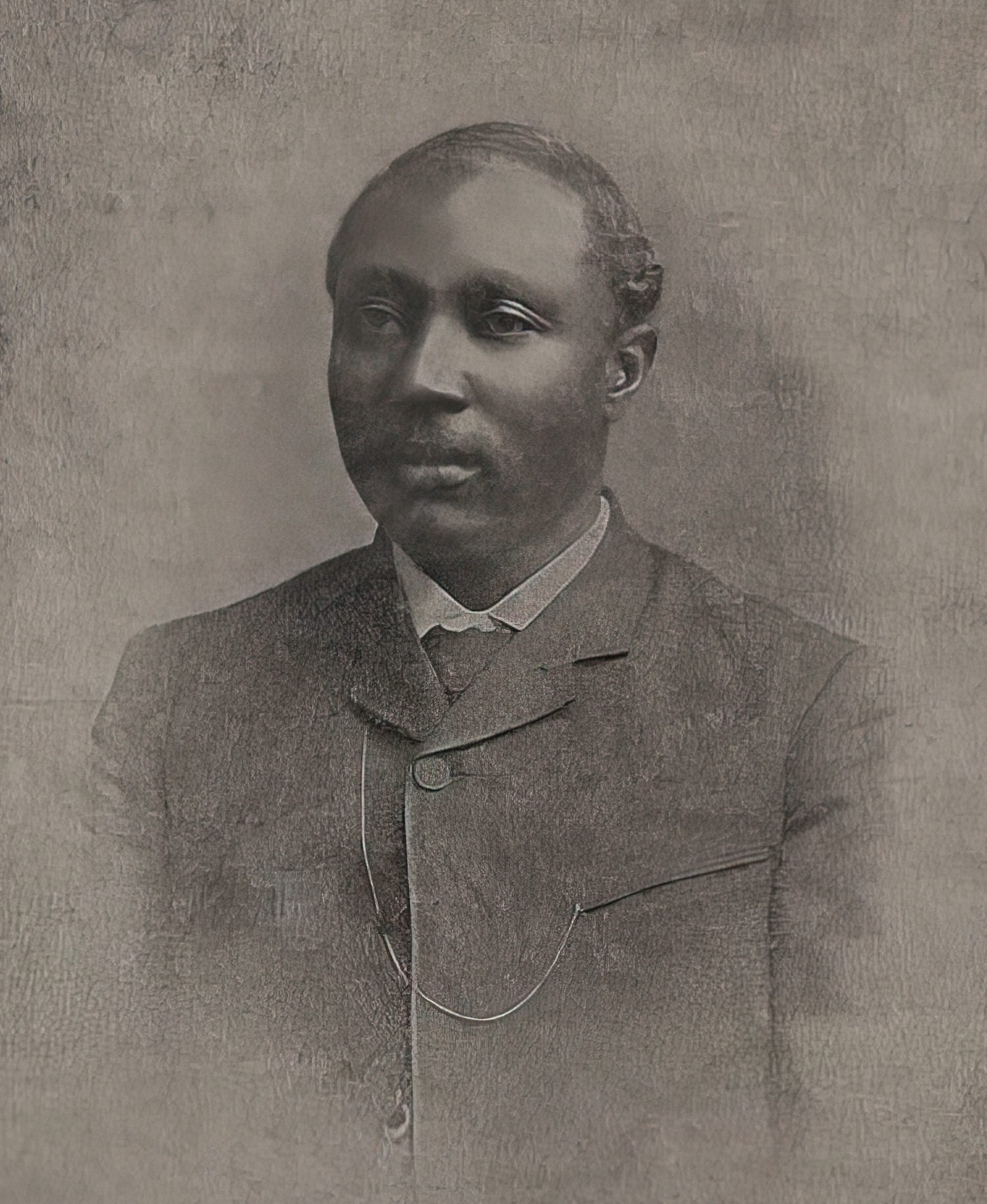

Thus, he dedicated his new congregations to St. Ignatius, St. Cyprian, St. Ambrose, St. Perpetua, St. Athanasius, as well as to the Messiah, Transfiguration, and St. Andrew. He founded six chapels along the Satilla River. He worked as far inland as Waycross, founding the Church of St. Ambrose there. Better known in his later years as a politician, journalist, and physician, Dr. Joseph Robert Love was the first black clergy person to serve in the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia. Born in the Bahamas on October 2, 1839, Love was educated at St. Agnes Parish School and Christ Church Grammar School in Nassau. He worked as a teacher before moving to Florida in 1866. In 1871, Bishop John F. Young of the Diocese of Florida ordained him a deacon. Later that year, he moved to Savannah, becoming the Deacon in Charge of St. Stephen’s Church. In 1872, citing discrimination in St. Stephen’s against those with darker skin color, he founded St. Augustine’s Church. Love moved to Buffalo, New York in 1876 to accept a call as Rector of St. Philip’s Church. While there, he was ordained a priest and then studied in the medical school at the University of Buffalo. In 1880, he was awarded his Doctor of Medicine degree, becoming the first black graduate of the school.

Better known in his later years as a politician, journalist, and physician, Dr. Joseph Robert Love was the first black clergy person to serve in the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia. Born in the Bahamas on October 2, 1839, Love was educated at St. Agnes Parish School and Christ Church Grammar School in Nassau. He worked as a teacher before moving to Florida in 1866. In 1871, Bishop John F. Young of the Diocese of Florida ordained him a deacon. Later that year, he moved to Savannah, becoming the Deacon in Charge of St. Stephen’s Church. In 1872, citing discrimination in St. Stephen’s against those with darker skin color, he founded St. Augustine’s Church. Love moved to Buffalo, New York in 1876 to accept a call as Rector of St. Philip’s Church. While there, he was ordained a priest and then studied in the medical school at the University of Buffalo. In 1880, he was awarded his Doctor of Medicine degree, becoming the first black graduate of the school. The Bright family’s friendship with Caroline Rathbone, a white woman who later became his daughter’s godmother, appears in an article detailing Rathbone’s funeral, held in Evansville, Indiana. A black man’s officiating at a white woman’s funeral raised eyebrows. “Colored Man to Take Part in Funeral at St. Paul’s Church” announced in The Evansville Courier, December 23, 1901. The article mentions Bright was once Rathbone’s Sunday School student in New York.

The Bright family’s friendship with Caroline Rathbone, a white woman who later became his daughter’s godmother, appears in an article detailing Rathbone’s funeral, held in Evansville, Indiana. A black man’s officiating at a white woman’s funeral raised eyebrows. “Colored Man to Take Part in Funeral at St. Paul’s Church” announced in The Evansville Courier, December 23, 1901. The article mentions Bright was once Rathbone’s Sunday School student in New York. Sewanee is now the University of the New South as one of the top small liberal arts colleges in the country. Georgia continues to be one of the owning Dioceses along with 27 other Southern Dioceses. The School of Theology is highly respected as is the School of Letters. Sewanee has 18,000 alumni for all 50 states and 40 countries and has produced 27 Rhodes Scholars and dozens of Fulbright Scholars. The Board of Trustees, the Faculty and Staff and the student body currently reflect the diversity and display the strength of that diversity. Sewanee is becoming the place where its motto can ring true: Ecce Quam Bonum “Behold how good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity.”

Sewanee is now the University of the New South as one of the top small liberal arts colleges in the country. Georgia continues to be one of the owning Dioceses along with 27 other Southern Dioceses. The School of Theology is highly respected as is the School of Letters. Sewanee has 18,000 alumni for all 50 states and 40 countries and has produced 27 Rhodes Scholars and dozens of Fulbright Scholars. The Board of Trustees, the Faculty and Staff and the student body currently reflect the diversity and display the strength of that diversity. Sewanee is becoming the place where its motto can ring true: Ecce Quam Bonum “Behold how good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity.” Born 1831 in Raleigh, North Carolina, Beckwith graduated from Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut in 1852. He served in North Carolina and Maryland before joining the staff of Confederate General William J. Hardee at the start of the Civil War.

Born 1831 in Raleigh, North Carolina, Beckwith graduated from Trinity College, Hartford, Connecticut in 1852. He served in North Carolina and Maryland before joining the staff of Confederate General William J. Hardee at the start of the Civil War. The lengthy address might have been easier on the ears than we first imagined. The Rev. Dr. Jimmy Lawrence in writing a history of the Diocese of Georgia in the early 1900s put it, “His wonderful voice, bringing out the full meaning of the services, at once arrested the attention of his hearers. When Bishop Beckwith read, people listened. His oratory in the pulpit attracted large congregations wherever he went, and the course of his episcopal visitations was like a royal progress.”

The lengthy address might have been easier on the ears than we first imagined. The Rev. Dr. Jimmy Lawrence in writing a history of the Diocese of Georgia in the early 1900s put it, “His wonderful voice, bringing out the full meaning of the services, at once arrested the attention of his hearers. When Bishop Beckwith read, people listened. His oratory in the pulpit attracted large congregations wherever he went, and the course of his episcopal visitations was like a royal progress.”