When Bishop Stephen Elliott founded the Diocese of Georgia’s first congregation for African Americans in Savannah in 1856, he placed it in the care of the Rev. Sherod W. Kennerly who also was in charge of the Savannah River Mission. Kennerly recruited an African American musician, James Porter, from Charleston to serve as musician and choirmaster for the new church. James’ mother, Martha Givens Porter, had been born enslaved in Charleston, but she used her skill as a dressmaker to save money to purchase her freedom, so James was born free around 1826. His father’s name is not recorded.

Because of an accident at an early age, James could not serve as a missionary as he later said he first felt called. Growing up in Charleston, he was able to study ancient and modern languages as well as vocal and instrumental music. With Kennerly’s encouragement, James and his second wife, Elizabeth, moved to Savannah in 1856.

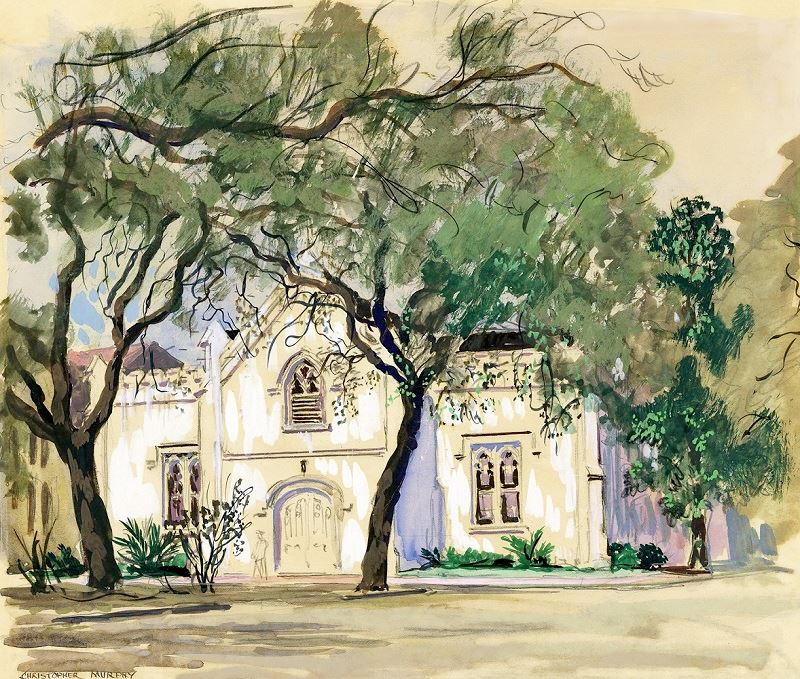

In 1859, the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia purchased the building owned by the Unitarian Church on Oglethorpe Square for St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church. As a history of Unitarians in Savannah states, “Since an African-American church on Oglethorpe Square was problematic in those days, the men of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church moved the building to Troup Square.” This gothic-inspired church (shown here in a painting by Christopher Murphy, Jr. from the W. W. Law Art Collection) was possibly designed by noted Savannah architect John Norris, though the architect may have only supervised its construction for the Unitarians.

In 1859, the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia purchased the building owned by the Unitarian Church on Oglethorpe Square for St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church. As a history of Unitarians in Savannah states, “Since an African-American church on Oglethorpe Square was problematic in those days, the men of St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church moved the building to Troup Square.” This gothic-inspired church (shown here in a painting by Christopher Murphy, Jr. from the W. W. Law Art Collection) was possibly designed by noted Savannah architect John Norris, though the architect may have only supervised its construction for the Unitarians.

In her study of the remarkable autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, first published in 1861 by escaped slave Harriet Jacobs, historian and biographer Jean Fagin Yellin notes that Porter used his business as a tailor and his music classes as a cover to secretly teach reading and writing in Savannah. This was dangerous in 1850s Georgia. The Rev. Charles L. Hoskins records in Yet With a Steady Beat that “Porter’s school ‘had a trap door where, when about to be surprised or apprehended, his pupils might save themselves.” The building where Porter worked as a tailor and taught was likely what is today 219 West Bryan. That building completed in 1855, adjoined one slave brokerage and was close to a second.

General William T. Sherman called a meeting with 20 black leaders in Savannah on January 12, 1865, with James Porter among them, described in the meeting’s notes as lay-reader and president of the board of wardens and vestry of St. Stephens, a congregation of about 200 persons. The African American leaders advised General Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton that freedom for enslaved former Africans would have to come with land to work on their own so they could live independently of their former owners. This led to Special Field Order Number 15 which set aside coastal islands for blacks. Some observers cite this meeting as the reason why James Porter never became a deacon in the Episcopal Church. Yet, later that same year Bishop Elliott wrote very favorably of the work being done at St. Stephen’s by James Porter, “a very intelligent and well-educated colored man, to whom I have given permission to read, without having actually licensed him in that capacity.” The Bishop said that the church had its own wardens (Porter was the Senior Warden) and vestry and was capably “managing its temporal affairs.”

Henry Malone’s History of the Episcopal Church in Georgia 1733-1957 states of Bishop Elliott’s funeral on Christmas Day 1866, “During the burial of Stephen Elliott, the colored vestry of St. Stephen’s Church demonstrated “touching and beautiful evidence of love and reverence they bore him.” They asked for and received permission to serve as pallbearers. An observer, Thomas A. Hanckel, commented on the incident: ‘Considering the peculiar and momentous issues of the time, we think it was the grandest and most instructive spectacle, amidst all the solemn, mournful and agitating ceremonies of the day, on which the city of Savannah was hushed to listen to the footfalls of those who thus bore their Bishop to the tomb.’”

After the war, Porter served as the principal of the Bryan Free School, which had as many as 450 students. The school met in the old Montmollin warehouse (at 21 Barnard Street today) which had been a place to hold and sell enslaved people. General Sherman confiscated the building and gave it to the African American community which formed the Savannah Education Association. The SAE opened the school on January 10, 1865. After the American Missionary Association consolidated a group of schools to form the Beach Institute in 1867, James moved to head the West Broad Street School, which started in what has been the Scarborough Mansion on that street.

Malone’s history records that in 1867, James Porter reported to the Diocese that his church membership numbered 87, with 40 enrolled in Sunday School. During the year three adults and eight infants were baptized; and nineteen communicants were added by confirmation. He stated that his routine was to read services “twice every Sabbath, and on other days specially set apart.” The Journal of the 45th convention of the Diocese in 1867 includes a report from the Standing Committee that they gave, “their consent as the Ecclesiastical Authority of the Diocese, to James Porter, colored, Lay Reader, by appointment of the late Bishop Elliott, at St. Stephen’s Chapel, Savannah, to make application for a recommendation to be received as a candidate for Deacon’s Orders.” They had this authority between the December 21, 1866 death of Bishop Stephen Elliott and the April 2, 1868 consecration of Bishop John W. Beckwith.

James Porter was elected a Republican member of Georgia state legislature from Chatham County, serving from 1868-1870. His tenure in the General Assembly was marked by working to get seated and then later reseated as he and other black legislators had to appeal to the federal government to be able to serve after the Democrats and Republicans worked together to try to have them expelled in 1868. During this time, The Rev. James Stoney, Rector of St. John’s Church served at St. Stephen’s with the assistance of the Rev. Samuel Minns, who would be described by Bishop Beckwith in 1873 as a “colored Priest, of the English church, from the Diocese of Nassau.”

Following his time in the state house, Porter pursued ordination in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. This move followed years of frustration from being denied holy orders even as he was permitted to serve as a lay reader without a license in the Episcopal Church. While it seems that Bishop Beckwith did not honor the Standing Committee’s approval, no clear record gives the reason for James Porter not being trained and admitted as a deacon in the denomination he long served. This is especially unclear as the church had enjoyed the ministry of a black priest previously and on James Porter’s departure, St. Stephen’s was served by a black Deacon in Charge, the Rev. Joseph R. Love. The notable difference being that these other clerics arrived in the Diocese already ordained.

Whatever the reason for not putting him forward for ordination, James Porter was successful with the A.M.E. Church, being ordained in Thomasville, Georgia, in 1879 at the age of 57. He had taken his first assignment as pastor in that town, where he also became the principal of the first public school in the city for its black residents. There he wrote an English Grammar for Beginners. His next assignment in the A.M.E. Church took him to Yazoo, Mississippi, where he once again served as principal of the public school for black students. He was later appointed to Florida, Arkansas, Bermuda, and finally Hamilton, Canada. Due to the death of his first two wives, James Porter was married three times, first to Christine Lazarus (c. 1849), then Elizabeth Paroley (c. 1853), and finally to Harriet R. (the date of the marriage and her maiden name are uncertain).

He was 73 when on a return trip from leading a service in Canada, Porter was removed from a train in New York, suffering from the flu. He died in New York City in late September of 1895. The Rev. James Ward Porter is buried in Laurel Grove Cemetery (South) in Savannah, Georgia, where he had buried his mother in 1877. The graveyard is near St. Matthew’s Episcopal Church, which was formed in the 1940s from a merger of St. Stephen’s and St. Augustine’s, the two traditionally African American Episcopal congregations in the city.

See also this biography: The Rev. James Porter

The biography of his grandson, a noted artist, may also be of interest: James Amos Porter, Artist