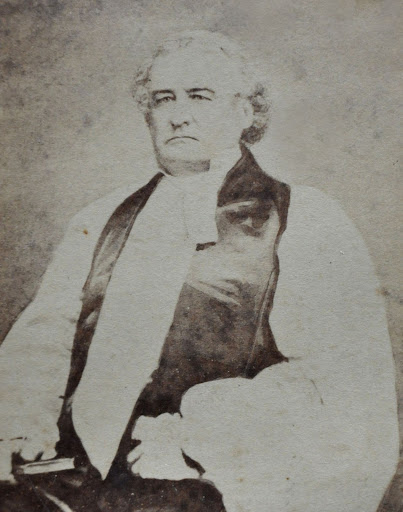

A sermon by the Rt. Rev. Stephen Elliott, First Bishop of Georgia given at Christ Church, Savannah on Thursday, September 15, 1864—The day of fasting, humiliation and prayer appointed by the Governor of the State of Georgia. Published by Burke, Boykin & Co. of Macon, Georgia.

PSALM LX. VV. 11, 12.

Give us help from trouble; for vain is the help of man.

Through God we shall do valiantly; for He it is that shall tread down our enemies.

Once again have we been summoned my beloved people, to bow ourselves in humiliation before God, and with fasting and prayer to invoke his intervention in our behalf. War and its attendant horrors have come very near our own homes, and we meet to-day to beseech our Heavenly Father that its bloody tide may be stayed, and its proud waters may not be permitted to roll over us. For months past has it been steadily advancing toward us; we have heard its hoarse and cruel murmuring as it came nearer and nearer; the spoils of its destructive progress have been brought to our feet in the exiled women and children who have fled to us for refuge, and in the dead bodies of our noble young men which have come back to us for Christian burial. But it has not yet reached us, and we unite to-day, with the citizens of our sovereign State, to pray that God would utter his decree, “Thus far shalt thou go and no further.” Trouble is near enough to us to make us earnest; already have the flutterings of distress disturbed many hearts; already is the enquiry frequent and anxious, ” What shall be the end of these things?” Man is looking to his fellow-man with gloomy face and troubled spirit. Woman is summoning up her fortitude to give her strength in the day of adversity. Our counsellors are at fault, and our armies have been steadily driven back. We cry unto man and no help comes; we labor and fight and there is no fruit of our labor, and no permanent success to our arms. We have nothing left but to follow the example of the Psalmist and crying unto God to “give us help from trouble,” to acknowledge that “vain is the help of man.”

But this is to us no new phase in our affairs. What have we been engaged in from the beginning but just this very confession that “our help must come from God,” and that “it is He that shall tread down our enemies.” Had I ever looked to the arm of flesh, I should never have hoped for any termination of this conflict but a fatal one. The odds against us were too great, unless we believed that God was on our side, and that his influences would equalize the conflict. Almost every six months since this struggle commenced, have we bowed ourselves, as a people, before the Lord of Hosts, and prayed for his mercy and protection from the fury of our mighty foes. And never have we cried in vain! He has always answered our supplications, and has thus far supported us under all our trials, and sustained our cause against the overwhelming masses of our enemy. Our case is no different now, save that the peril and the desolation have become more personal to ourselves, and that we feel its presence more sensibly. We clothed ourselves in mourning then for the Confederacy; we now keep our day of humiliation for the State. We fasted and prayed to the Lord of Hosts upon those occasions for the general cause. We now are in bitterness for our own fair heritage, and for the sufferings of our personal friends, and for the slaughter of those who are near and dear to us. Louisiana and Mississippi, and Arkansas and Tennessee, and above all, high souled Virginia, have all passed through the desolation which seems approaching us; have all wept over their ruined homes and their despoiled estates; have carried their loved ones to the grave with firm hearts and unshaken spirits, sustained by the assurance that they have died in the noblest cause in which blood can be shed, or life poured out. They are still unconquered; the wave has passed over them, but has not overwhelmed them; they have shaken its waters from them, as the Lion shakes the rain drops from its mane, and yet breathe defiance and maintain hope. No new thing has happened unto us. We are only passing through the fiery trial which has tried most of our sister States, and while it is right that we should humble ourselves before God, and implore his help in our day of necessity, it is also right that we should imitate the proud example of those desolated States, and prove that we are worthy to be classed among the sovereignties which can suffer and die, but cannot pass under the yoke of servitude.

But this is to us no new phase in our affairs. What have we been engaged in from the beginning but just this very confession that “our help must come from God,” and that “it is He that shall tread down our enemies.” Had I ever looked to the arm of flesh, I should never have hoped for any termination of this conflict but a fatal one. The odds against us were too great, unless we believed that God was on our side, and that his influences would equalize the conflict. Almost every six months since this struggle commenced, have we bowed ourselves, as a people, before the Lord of Hosts, and prayed for his mercy and protection from the fury of our mighty foes. And never have we cried in vain! He has always answered our supplications, and has thus far supported us under all our trials, and sustained our cause against the overwhelming masses of our enemy. Our case is no different now, save that the peril and the desolation have become more personal to ourselves, and that we feel its presence more sensibly. We clothed ourselves in mourning then for the Confederacy; we now keep our day of humiliation for the State. We fasted and prayed to the Lord of Hosts upon those occasions for the general cause. We now are in bitterness for our own fair heritage, and for the sufferings of our personal friends, and for the slaughter of those who are near and dear to us. Louisiana and Mississippi, and Arkansas and Tennessee, and above all, high souled Virginia, have all passed through the desolation which seems approaching us; have all wept over their ruined homes and their despoiled estates; have carried their loved ones to the grave with firm hearts and unshaken spirits, sustained by the assurance that they have died in the noblest cause in which blood can be shed, or life poured out. They are still unconquered; the wave has passed over them, but has not overwhelmed them; they have shaken its waters from them, as the Lion shakes the rain drops from its mane, and yet breathe defiance and maintain hope. No new thing has happened unto us. We are only passing through the fiery trial which has tried most of our sister States, and while it is right that we should humble ourselves before God, and implore his help in our day of necessity, it is also right that we should imitate the proud example of those desolated States, and prove that we are worthy to be classed among the sovereignties which can suffer and die, but cannot pass under the yoke of servitude.

Why should we, of all the States of the Confederacy have hoped to be exempt from suffering? Are we better than they? Have we a higher tone of morality and religion than that proud mother of States for example, who has for three years been the battle ground of the revolution? Her cities have been captured, and placed under the iron heel of the vilest fanatics of the age; her rural population has been driven from their beautiful homes, and are now wanderers over the Confederacy; her Churches, sacred relics of the past, around which are clustered the graves of generations, have been burned with fire; her archives, memorials of the long line of her heroes and statesmen, a loss irreparable, have been rifled and destroyed. Has she quailed before these things? Have her hands been made to hang down and her knees to become feeble? Has she even complained? Why should we expect to escape our share of the punishment which comes from God, especially when that punishment seems to be the chastening of a Father and not the judgment of a consuming fire? Nay more, should we desire it? Are we self-righteous enough to imagine that we do not deserve our share of the chastisement which is abroad? God forbid! for it would prove that we were in a condition which might demand a fiercer cautery. Better for us to share our portion of the passing evil, than to be spared, in the future, for some sorer punishment. Were we to come out of this conflict, alone of all the States, rich, unharmed, undevastated, we should come out without a local history, without any thing for tradition to hang glory upon, without those scars of honor which designate the veteran hero. We might be pointed at as a State which had reaped nothing but gain from the conflict, and had accumulated wealth at the expense of the sufferings of others. We might be left with a sordid spirit, caring more for money than for honor, more for gain than for reputation. Better, far better for us, as a State, that we should bear our portion of the general suffering, should be able to point to battle fields hotly contested upon our own soil, should have tales to tell in the future which would prove us to have been an heroic race, and not distinguished alone for our powers of acquisition, and our habits of trade. A national character is a most important element in the future of a State, and in no way is it so certainly gained as by passing a people through a fierce struggle, in which they have been brought face to face with suffering and peril. All those States which in the old revolution bore the brunt of the British fury, have to this day maintained their reputation, and have stood conspicuous upon the pages of our public history, Massachusetts, New York, Virginia, South Carolina! Their battle fields have made them historical, and they have kindled within them, ever since, a national feeling which has helped to make them conspicuous. It operates upon States, as a line of heroic and renowned ancestry operates upon individuals. Just as the French proverb, “Noblesse oblige,” marks the effect upon the individual whom nobility distinguishes, so does the history of a State operate upon its people. Their past requires a present which shall be correspondent with its fame, and harmonious with its character. The eye of the world is upon them; they know it and feel it, and they rise up, under the consciousness, to a level very much above that which, under ordinary circumstances, they should have attained. Even under this point of view, the invasion of our State is not so great a calamity as many feel it to be; individuals may suffer deeply, but the State may be elevated immeasurably; our fields may be sown with blood and desolation, but the harvest may be one of national character which shall bless us for long generations.

But putting aside this view of the subject, may we not have expected just such a visitation? Have not our own statesmen and orators been predicting, for the last eighteen months, just such results as the consequences of the iron grasp with which many of our citizens have clung to their property and their ease? Has not the voice of the truest of our patriots, [Howell Cobb] been ringing through the State exhorting our people to feed our armies, to clothe our soldiers, to furnish to the Government the necessary material of war? Have not his words of power and of sarcasm been hurled in vain against these very men who are now likely to lose the whole because they would not yield a part to the just demands of their country? Have not our Generals in command cried for men and cried without any answer, until the strong arm of power has been obliged to drag them from their skulking places and force them to their duty? What can our State expect but subjugation, if her citizens will not consent to supply our armies with food and with men? We think upon an occasion like this, when a foe is upon us, whom we now clearly understand to have determined to extirpate our race as a pestilent one, and to fill up the seats of our ancestors with hirelings from every land under the sun, that every sword would leap from its scabbard, every arm would acquire fresh power, and in one solid phalanx we would arise and annihilate the invader. If we do not we deserve our fate and it will come upon us justly. We should fast and pray, but not for our danger; our humiliation should be for our covetousness, for our low-mindedness, for our indifference, for our apathy. If the Lord answers us aright, his answer would be that which he made to Moses, when the people of Israel were crying unto him from among the mountains of the Red Sea, and were saying, “Is not this the word that we did tell thee in Egypt, saying, let us alone that we may serve the Egyptians? For it had been better for us to serve the Egyptians, than that we should die in the wilderness?” “Wherefore criest thou unto me? Speak unto the children of Israel, that they go forward!” Yes, this is what we are called to fast and pray for, that we have not the liberality to pour out food for the necessities of our Government, nor the manliness to unite as one man and hurl our foe across the borders. It requires nothing but the resolution; the act would follow it as certainly as united Greece rolled back the myriads of the Persians. No army has ever yet been able to withstand a people rising in its power. Even Napoleon, in the heigth of his dominion, quailed before regenerate Germany, when Körner awoke his people to resistance by the magic of his song, and the Father-land was free!

There is no inconsistency, my hearers, between saying that, “the help of man is vain,” and “that it is God who is to tread our enemies under foot,” and yet calling upon our people to awake and buckle on the armor of heroic citizenship! God works by means; we must not expect in these days, to receive help from Him through miracle. He will help us in time of trouble, but through ordinary means. He will help us by giving us strength in the day of adversity; by opening our hearts to sustain our Government; by quelling dissensions among ourselves; by infusing courage into all those who are weak-minded and timid; by confounding the devices of our enemies. These are the ways in which he now manifests himself, and it is for these ends that we are called to fast and to pray this day. If any one expects that the results of this humiliation will exibit themselves in some extraordinary shape, he will be sorely disappointed. If any results flow from it, and they will be dependent upon the sincerity and faithfulness with which it is observed, they will come in the shape of renewed faith, of enlarged hope, of fresh confidence, of reviving courage. They will be seen in the readiness with which our people will rally around the Government—in the healing of dissensions among our authorities—in the decrease of selfishness—in the determination of every one to do his part, whatever it may be, in flinging back, into the face of our enemies, his insults and his cruelty. These are the legitimate consequences of humiliation and prayer, because these are the means which are natural and which God is accustomed to use in these days when miracles are no more required. Our text combines the two very beautifully. “Through God we shall do valiantly,” is its expression. It is we who are to do valiantly, but yet it is through God. And so shall we find it. He means us to work out our own deliverance, but to work it out in subjection to his will and in subservience to his purposes. He will be the sovereign ruler of his people, even while he may be guiding them to their heart’s desire.

In this conflict, more perhaps than in any the world has seen, must it be God who shall tread under foot our enemies. It is a conflict involving the future of a race, whose existence or extinction depends upon its result. The white race of the South, even though subjugated might continue to exist, to live on for a time in shame and degradation, and at last to commingle, as the Anglo-Saxons did, with their Norman conquerors. But the black race perishes with its freedom. They will die out before the encroaching white labor of Europe, which will be poured in upon them, as the Indians have died out before the progress of civilization, or they will be banished to other lands to perish there, forgotten and unlamented. The Puritan code of mercy has always been the harsh one, “If you cannot do for yourself you must die.” If God therefore has any meaning in his past dealings with this race, in permitting it to be brought here, to be preserved, to increase, to be civilized, it is not his purpose that they should be given the liberty which their pretended friends are seeking for them. To protect them, he must protect us, and therefore is it, as I have said again and again, that I have full confidence in the successful termination of this conflict. What we may suffer in the struggle is one thing; the end of the struggle is quite another thing. And looking at it in this light I am not disturbed by temporary successes or defeats on the one side or the other; nor am I elated by appearances which seem to promise us any help from man. This is God’s war; he has conducted it upon very remarkable principles; and he will terminate it in his own way and just when he thinks that the ends have been worked out which He designs to fulfil. Let us consider these points before we close.

The two ends which be seems to have had in view in the permission of this terrible war have been the punishment, in a natural way of an arrogant people, who were ascribing their prosperity and their material power, not to his loving kindness and divine mercy, but to their institutions and the liberty upon which they were founded, and then the discomfiture of the short-sighted philanthropists of the world, who conceiving themselves to be wiser and more merciful than God, had determined to blot out of the world all the evils which sin and the curse had laid upon it, and especially the evil of slavery. Now was the time for this glorious work! The South had laid itself open to their assaults by her secession, and the axe must be laid at the root of the tree. This war, continued now for more than three years with unparalleled bloodshed, is the mode in which God is accomplishing his purposes. Our punishment is, as I said to you a few Sundays since, a dispensation of death. This war has produced no results but slaughter and bloodshed. God has conducted it upon such principles, as that while death has reigned triumphant, no permanent success has crowned either side. All its great battles have produced no results looking to any settlement of this dispute. At the first battle of Manassas we gave the enemy a shameful defeat; disgraced and panic stricken he fled to his Capital; and we held victory in our grasp, but it was fruitless in its consequences. Our great defeats in the West, the capture of New Orleans, the overrunning of Louisiana, Arkansas and Mississippi, have in like manner been fruitless in their hands. We have recovered almost every thing which we lost, and all that remains of those bloody fights are the graves which furrow the banks of the Mississippi and the bones which are bleaching upon its plains. The wheel of fortune again turned in our favor, and Lee’s great victories in Virginia, in 1863, were rendered without permanent benefit by our failures on the other side of the Potomac. We reaped a harvest of death and nothing else. And so will it continue until God’s wrath is satisfied, and therefore have I not been disturbed by our recent reverses. They mean blood and death and nothing more. Subjugation is as far off as it ever was and never can take place, for God’s other purpose interferes with it, and his purpose must rule.

That other purpose, as I said before, is the discomfiture of the so called philanthrophy of the world—its discomfiture by showing it practically how little the slaves care for such freedom as they can offer, and that the tender mercies of such friends are cruel. The bitterest disappointment of this war has been the quiet contentment of the slaves. They have never gone to our enemies in any numbers; deceit and cajolement have been used in vain; they have had to come to the slave. He has continued in obedience through all the changes of the struggle, and never yet has offered violence to those who have had charge of him. Their quiet has been wonderful even to ourselves, and has caused the world not only to wonder, but to reverse its settled judgment about their treatment and condition. And how sad has been their fate since they have been beguiled and betrayed into the hands of their so called liberators! The husbands and sons perishing by thousands upon the battle field, and the wives and mothers and little children sinking into inhospitable graves with none to care for them or watch over them. I will venture to say that of the negroes who have fallen under the dominion of the Federal armies, more than one-half of those who have been deprived of the protection of their masters have already perished. The world even now sees and acknowledges that the slaves have gained nothing by their emancipation, and are beginning to be satisfied that it has made a grievous mistake in attempting to remove these people from their normal condition of servitude.

When these two purposes shall have been effected, our punishment through the dispensation of death, and the overthrow of man’s folly and fanaticism, then may we look for peace—and not until then! Therefore is it that I repeat, “Vain is the help of man.” I have no faith in national platforms and Presidential elections; no expectations from European recognition or foreign interference; no trust in the power of cotton, or in the failure of money. I look to God for His help, and in due time it will come. Meanwhile we must be patient and enduring–patient under his chastisements, and enduring while he is making things work together for good to us. As I have said to you, again and again, this war is never to be ended by any victories of ours; God will give us just enough of them to enable us to keep our enemy at bay; it will be ended by his turning their arms inward upon themselves. In the punishment of Europe for its horrid blasphemy, infidelity, and vice of the last century, that punishment took the same form of a dispensation of death. The French Revolutionists slaughtered their fellow citizens at home until they were glutted with blood, and man could endure no more; then the carnage was carried on still upon themselves, but likewise upon their neighbors, who had abetted their sins, through the wars of Napoleon. Upon our continent the punishment has been reversed; the people of the Northern States had been trained upon such principles of law and order, that they were not prepared at once, to cut each other’s throats; they must first be accustomed to violence through years of bloody war, and grievances must be created great enough to excite their angry passions. The dispensation of death upon this continent, has taken, therefore, a different course; first outward upon us, and then inward upon themselves. When God is satisfied with our chastisement, and we, in humble penitence and submission have said, “Give us help from trouble; for vain is the help of man,” then will He permit our sufferings to cease and theirs to begin. They need not boast that they do not feel the war; they need not exult in their wealth and luxury; they are only fattening in a large place as a lamb for the slaughter. Their feet shall slide in due time. The election of Lincoln is a necessity for our deliverance; any other result should be disastrous to us. We need his folly and his fanaticism for another term; his mad pursuit of his peculiar ideas. It is he that is ordained to lead his people to destruction; to force them into conflict through the arbitrariness of his decrees. His re-election will give him fresh courage and additional madness. He will drive all sound and rational men from his side; he will gather around him the radical and the fanatic; he will pursue the war with redoubled fury, until at last satiated with misrule, the sober thinking men of the North will perceive, that submission to him is utter and perpetual ruin. Then will come the conflict which shall deliver us, when we shall be obliged to confess, (for it may not come until we are in our last extremity); “It is the Lord’s doing, and it is marvellous in our eyes.” All things are working together for our good. The fall of Atlanta, the victories at Mobile, our reverses of whatever kind, are so many links in the re-election of Lincoln, and therefore, so many links in the chain of our deliverance. Every thing which gives them confidence, is so much in our favor, because it goads them on in their career of madness. What we have most to fear in our exhausted and depressed condition, is an administration which would come with kindness on its lips, and reconstruction with our ancient privileges in its hand. I fear our people would not have virtue to resist it, and we should be linked once more to that “body of death.” What we require is such fury as Grant’s, such cruelty as Butler’s, such fanaticism as Sherman’s. It is men like these who revive our courage, and reanimate our efforts. We see that we have nothing to look for but degradation and outlawry; that we must fight, or else give up every thing that an honorable man holds dear—not only our property, but our caste—not only our sovereignty, but our personal freedom. When we realize fully what our future condition is to be, and Lincoln’s re-election will make us realize it, then shall we be fairly aroused, and must make the choice between a perpetual resistance, if necessary, and a condition of serfdom, in which we and our children shall be made “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” to the paupers of Europe, the negroes of Africa, and last and lowest of all, to the Black Republicans of the North. If any of you are ready for that, I am not, and therefore I cry unto God to help me in trouble, “for He it is who is to tread down our enemies.”