In fall of 1864, the crushing news of the Fall of Atlanta to the massive assault of General Sherman’s Federal troops was just three weeks old. Sherman’s devastating March to the Sea was underway. The weight of this devastation is revealed in the change of name for our Episcopal church in Americus. In the 1850s, Bishop Stephen Elliott sought to found St. John’s Episcopal Church in Americus with nine communicants. That church start failed.

When the same bishop founded a church in Americus six years later, he selected the name Calvary, reflecting the suffering he had seen up close.

Bishop Stephen Elliott had visited the Army of the West back in 1863, when they were encamped at Shelbyville, Tennessee. He confirmed ten in a liturgy held at the Presbyterian Church. Elliott wrote “The attention of this large body of soldiers was earnest and like men who were thoughtful about their souls. It gave hope for the future of both the army and the church.”

Bishop Stephen Elliott had visited the Army of the West back in 1863, when they were encamped at Shelbyville, Tennessee. He confirmed ten in a liturgy held at the Presbyterian Church. Elliott wrote “The attention of this large body of soldiers was earnest and like men who were thoughtful about their souls. It gave hope for the future of both the army and the church.”

The fortunes of war turned. The fight came to Georgia. Bishop Elliott again visited the troops as close as he could get to the battle lines. In the summer of 1864, his friend and fellow bishop, Leonidas Polk, died by canon shot when he and other generals were scouting Federal troop positions near Marietta. We get a glimpse of this time in Bishop Elliott’s Diocesan Convention Address of 1866, given eleven months after he founded Calvary which he began saying:

“Brethren of the Clergy and Laity: Another eventful period has passed away—“a period of darkness and of gloominess, of clouds and thick darkness”—during which our Lord has moved among us in awful mystery and in seeming wrath. The tumultuous tide of events has rolled very contrary to our wishes and our anticipations; has been freighted with a heavy burden of sorrow, and suffering, and death, and has brought us together this day with trouble all around us, with cruel anxieties pressing upon us, with grave perplexities entangling us, with very little joy or hope save such as may spring from a divine source.”

With heavy loss of life and destruction close at hand, the Episcopal Church in Americus was named Calvary. As Christians, we have no stronger image to summon in times of darkness. For though Jesus could cry out from the cross, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” We can see the Civil War differently from our first bishop and yet share his conviction that nothing can separate us from the love of God that is found in Christ Jesus.

With heavy loss of life and destruction close at hand, the Episcopal Church in Americus was named Calvary. As Christians, we have no stronger image to summon in times of darkness. For though Jesus could cry out from the cross, “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” We can see the Civil War differently from our first bishop and yet share his conviction that nothing can separate us from the love of God that is found in Christ Jesus.

Bishop Elliott’s choice of Calvary would have felt apt to the congregation. The twenty-one communicates were very aware of the Confederate Hospital in Americus where some served. The most terrible of Prisoner of War camps was just thirteen miles away in Andersonville. Those who knew him said the loss of the Confederacy devastated Bishop Elliott. He died suddenly on December 21, 1866, on returning home from what proved to be his final episcopal visitation.

The pictures above show part of the Battle for Atlanta and Andersonville Prison, just north of Americus.

President Jefferson Davis declared Friday, March 27th, 1863, to be a Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer. Bishop Stephen Elliott Jr. preached on that occasion at Christ Church, Savannah, “War is a great eater, a fierce, terrible, omnivorous eater. It eats out wealth, property, life…,.it devours religion, and tramples under foot its temples and its altars–it rides in desolation upon the storm of passion and the whirlwind of vengeance.

President Jefferson Davis declared Friday, March 27th, 1863, to be a Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer. Bishop Stephen Elliott Jr. preached on that occasion at Christ Church, Savannah, “War is a great eater, a fierce, terrible, omnivorous eater. It eats out wealth, property, life…,.it devours religion, and tramples under foot its temples and its altars–it rides in desolation upon the storm of passion and the whirlwind of vengeance. As many influential Episcopalians in the north saw slavery as a political or legal question rather than a moral one, no such rancorous debate took place in our church. When southern states seceded from the Union, the situation changed. In 1861, Bishop Stephen Elliott of Georgia joined Bishop Leonidas Polk of Louisiana in writing a letter to southern dioceses calling for a church council. In that letter, the bishops said, “We rejoice to record the fact, that we are today, as Churchmen, as truly brethren as we have ever been; and that no deed has been done, nor word uttered, which leaves a single wound rankling in our hearts.”

As many influential Episcopalians in the north saw slavery as a political or legal question rather than a moral one, no such rancorous debate took place in our church. When southern states seceded from the Union, the situation changed. In 1861, Bishop Stephen Elliott of Georgia joined Bishop Leonidas Polk of Louisiana in writing a letter to southern dioceses calling for a church council. In that letter, the bishops said, “We rejoice to record the fact, that we are today, as Churchmen, as truly brethren as we have ever been; and that no deed has been done, nor word uttered, which leaves a single wound rankling in our hearts.” In November 1862, the first General Council of the church met at Saint Paul’s in Augusta. Most of the bishops in the Confederate States gathered there again in June 1864 as Bishop Elliott preached at the funeral for Bishop Leonidas Polk, who served as a general in the war and died in battle.

In November 1862, the first General Council of the church met at Saint Paul’s in Augusta. Most of the bishops in the Confederate States gathered there again in June 1864 as Bishop Elliott preached at the funeral for Bishop Leonidas Polk, who served as a general in the war and died in battle. The Butler Family owned significant property on St. Simons Island and rice growing land on and around Butler Island, south of Darien. Major Pierce Butler (1744-1822) accumulated great wealth that, as he was estranged from his son, went to two grandsons on his death—Pierce and John. The younger Pierce speculated in business experiencing dramatic losses in the Panic of 1857. Compounding these losses were gambling debts. Butler had to transfer his estate to Trustees for a sale to cover $700,000 in debt. This is calculated at more than $22.8 million of losses in today’s dollars. The Trustees sold his Philadelphia Mansion for $30,000. Even with other real estate, they could not satisfy creditors. His greatest wealth was invested in what was considered “human capital.”

The Butler Family owned significant property on St. Simons Island and rice growing land on and around Butler Island, south of Darien. Major Pierce Butler (1744-1822) accumulated great wealth that, as he was estranged from his son, went to two grandsons on his death—Pierce and John. The younger Pierce speculated in business experiencing dramatic losses in the Panic of 1857. Compounding these losses were gambling debts. Butler had to transfer his estate to Trustees for a sale to cover $700,000 in debt. This is calculated at more than $22.8 million of losses in today’s dollars. The Trustees sold his Philadelphia Mansion for $30,000. Even with other real estate, they could not satisfy creditors. His greatest wealth was invested in what was considered “human capital.” The Trustees netted $303,850 in the auction. A mother and her five grown children brought the highest bid, $6,180 with most people selling for prices from $250 to $1,750. Though the tragedy of this sale disturbs us, sentiment at the time favored Butler as one Philadelphia friend, Sidney George Fisher, entered into his diary, “It is highly honorable to [Butler] that he did all he could to prevent the sale, offering to make any personal sacrifice to avoid it.”

The Trustees netted $303,850 in the auction. A mother and her five grown children brought the highest bid, $6,180 with most people selling for prices from $250 to $1,750. Though the tragedy of this sale disturbs us, sentiment at the time favored Butler as one Philadelphia friend, Sidney George Fisher, entered into his diary, “It is highly honorable to [Butler] that he did all he could to prevent the sale, offering to make any personal sacrifice to avoid it.” Bishop Stephen Elliott personally trained and then ordained the Rev. William C. Williams to serve as the pastor for what became the Ogeechee Mission. Williams established a school and a chapel on each of the three plantations he then served. Williams reported to diocesan convention on his work in 1846 saying,

Bishop Stephen Elliott personally trained and then ordained the Rev. William C. Williams to serve as the pastor for what became the Ogeechee Mission. Williams established a school and a chapel on each of the three plantations he then served. Williams reported to diocesan convention on his work in 1846 saying, By 1860 his congregation was the largest in the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia. This was not the only congregation founded on plantations. In 1851, Bishop Elliott reported to convention on the work of the Rev. James H. George, a Deacon, who took charge of a mission in the Albany area. The deacon divided his time among three stations on neighboring plantations owned by Episcopalians. First St. Paul’s and later St. John’s in Albany were the result of that work.

By 1860 his congregation was the largest in the Episcopal Diocese of Georgia. This was not the only congregation founded on plantations. In 1851, Bishop Elliott reported to convention on the work of the Rev. James H. George, a Deacon, who took charge of a mission in the Albany area. The deacon divided his time among three stations on neighboring plantations owned by Episcopalians. First St. Paul’s and later St. John’s in Albany were the result of that work. Bishop Elliott adopted a plan inconceivable today as the church school was to be founded around the work of enslaved Africans. He wrote that this scheme had worked for many years on the island of Barbados. The Montpelier Institute, with both boys and girls schools on an 800-acre campus was to be a working farm staffed by enslaved persons. Their work was to pay the bulk of the costs of the school. He saw additional advantage for the students in studying on a farm writing, “They will also be trained in the best mode of performing their duties as the owners of slaves and the masters of human beings for whose souls they must give an account.”

Bishop Elliott adopted a plan inconceivable today as the church school was to be founded around the work of enslaved Africans. He wrote that this scheme had worked for many years on the island of Barbados. The Montpelier Institute, with both boys and girls schools on an 800-acre campus was to be a working farm staffed by enslaved persons. Their work was to pay the bulk of the costs of the school. He saw additional advantage for the students in studying on a farm writing, “They will also be trained in the best mode of performing their duties as the owners of slaves and the masters of human beings for whose souls they must give an account.” By 1846, Elliott was living on the school grounds and reported that he had accomplished more Bishop’s visits in the previous year than in the years before moving to centrally-located Institute. By that time, more than 80 students were enrolled in the two schools which formed the Montpelier Institute. The rapid expansion of the school including the completion of more buildings amassed debt. Never funded by the Diocese, Elliott used his personal property, including “human capital” of enslaved persons, as a guarantee. In 1850, Elliott lost everything he owned. He sold all of his land and his considerable holdings in enslaved persons to satisfy the school’s creditors.

By 1846, Elliott was living on the school grounds and reported that he had accomplished more Bishop’s visits in the previous year than in the years before moving to centrally-located Institute. By that time, more than 80 students were enrolled in the two schools which formed the Montpelier Institute. The rapid expansion of the school including the completion of more buildings amassed debt. Never funded by the Diocese, Elliott used his personal property, including “human capital” of enslaved persons, as a guarantee. In 1850, Elliott lost everything he owned. He sold all of his land and his considerable holdings in enslaved persons to satisfy the school’s creditors. Elliott saw himself as that ox ready to do whatever God demanded of him. The seal shows two dates with 1733 noting the arrival of the first Anglican priest along with Georgia’s first colonists and 1823 as the date the Diocese of Georgia was organized with three parishes. The Diocese would not elect Elliott as our first bishop and gain the seal he created until 1841 when the diocese comprised the requisite six congregations needed to organize formally.

Elliott saw himself as that ox ready to do whatever God demanded of him. The seal shows two dates with 1733 noting the arrival of the first Anglican priest along with Georgia’s first colonists and 1823 as the date the Diocese of Georgia was organized with three parishes. The Diocese would not elect Elliott as our first bishop and gain the seal he created until 1841 when the diocese comprised the requisite six congregations needed to organize formally. Bishop Elliott would repeat the motto in later addresses to convention, always as a rallying cry to the patient, steady work needed to advance the Gospel in Georgia saying that “a harvest will come, though his successor may reap the fruits of it.”

Bishop Elliott would repeat the motto in later addresses to convention, always as a rallying cry to the patient, steady work needed to advance the Gospel in Georgia saying that “a harvest will come, though his successor may reap the fruits of it.” Baker wrote of the event, “I received a pressing invitation to visit Beaufort. I went; and there being no Presbyterian church in the place, I preached alternately in the Baptist and Episcopal churches. The Episcopal minister, the Rev. Mr. Walker, was very cordial, and offered me the use of his pulpit. Knowing the peculiar views of our Episcopal brethren, I proposed standing below; but he insisted upon it that I should go into his pulpit.”

Baker wrote of the event, “I received a pressing invitation to visit Beaufort. I went; and there being no Presbyterian church in the place, I preached alternately in the Baptist and Episcopal churches. The Episcopal minister, the Rev. Mr. Walker, was very cordial, and offered me the use of his pulpit. Knowing the peculiar views of our Episcopal brethren, I proposed standing below; but he insisted upon it that I should go into his pulpit.” Of the eighty persons who experienced a conversion experience at St. Helena’s during that revival were eight men who became ministers. Among these was Elliott, who would a decade later become the first bishop of Georgia. Born in Beaufort, South Carolina, to one of the Low Country’s most powerful slaveholding families, Elliott attended his father’s alma mater, Harvard, for one year before coming back to study closer to home. He graduated from South Carolina College in 1825 and practiced law until his conversion experience when Elliott began to study for holy orders. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1836, having been ordained a deacon the previous year. He taught religion at South Carolina College from 1835-1841.

Of the eighty persons who experienced a conversion experience at St. Helena’s during that revival were eight men who became ministers. Among these was Elliott, who would a decade later become the first bishop of Georgia. Born in Beaufort, South Carolina, to one of the Low Country’s most powerful slaveholding families, Elliott attended his father’s alma mater, Harvard, for one year before coming back to study closer to home. He graduated from South Carolina College in 1825 and practiced law until his conversion experience when Elliott began to study for holy orders. He was ordained to the priesthood in 1836, having been ordained a deacon the previous year. He taught religion at South Carolina College from 1835-1841. In Georgia, the Creeks to the south and Cherokees to the north were seen not just as trade partners, but targets for missionary efforts including those by Anglicans like the Revs. John Wesley and Bartholomew Zouberbuhler. Later the Indigenous people were viewed as obstacles to be removed. The 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War set the westward boundary of Georgia as the Mississippi River. President George Washington negotiated with the Creeks the Treaty of New York in 1790 that moved the western boundary to the Oconee River just west of Athens. In 1802, politicians brokered a deal to have Georgia cede lands west of the Chattahoochee in exchange for getting what is the familiar map of the state. Georgia’s legislature spent the next 25 years calling on one president after another to make good on a pledge to “extinguish the Indian title to all other lands within the States of Georgia.”

In Georgia, the Creeks to the south and Cherokees to the north were seen not just as trade partners, but targets for missionary efforts including those by Anglicans like the Revs. John Wesley and Bartholomew Zouberbuhler. Later the Indigenous people were viewed as obstacles to be removed. The 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War set the westward boundary of Georgia as the Mississippi River. President George Washington negotiated with the Creeks the Treaty of New York in 1790 that moved the western boundary to the Oconee River just west of Athens. In 1802, politicians brokered a deal to have Georgia cede lands west of the Chattahoochee in exchange for getting what is the familiar map of the state. Georgia’s legislature spent the next 25 years calling on one president after another to make good on a pledge to “extinguish the Indian title to all other lands within the States of Georgia.”  As anticipation built for the cruel removal of the Cherokee Nation along what is now known as The Trail of Tears, Episcopalians planned their next steps. The Episcopal Church sent the Rev. John Hunt as a missionary to Clark County. The Rev. Edward Neufville, Rector of Christ Church, Savannah, and President of the Standing Committee also made a seven-month tour of the newly opening land. He officiated occasionally, as opportunity offered, for “the scattered members of our communion and others who were destitute of regular ministration.” Neufville noted that “Clarkesville and Milledgeville present a field for Missionary labour.” The pattern continued across the state as native peoples were forced out, other denominations arrived with pioneers with Episcopal Churches established years later.

As anticipation built for the cruel removal of the Cherokee Nation along what is now known as The Trail of Tears, Episcopalians planned their next steps. The Episcopal Church sent the Rev. John Hunt as a missionary to Clark County. The Rev. Edward Neufville, Rector of Christ Church, Savannah, and President of the Standing Committee also made a seven-month tour of the newly opening land. He officiated occasionally, as opportunity offered, for “the scattered members of our communion and others who were destitute of regular ministration.” Neufville noted that “Clarkesville and Milledgeville present a field for Missionary labour.” The pattern continued across the state as native peoples were forced out, other denominations arrived with pioneers with Episcopal Churches established years later.

In February 1823, the three Episcopal congregations in Georgia–Christ Church in Savannah, Saint Paul’s in Augusta, and Christ Church Frederica on St. Simons Island–sent delegates to the first convention of what became the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of Georgia. They celebrated the Eucharist together and prayed Morning Prayer daily through the February 24-28 convention. The delegates elected a Standing Committee, deputies to the General Convention of the Episcopal Church, and wrote the Constitution and Canons for the Diocese. They also founded “The Protestant Episcopal Society for the General Advancement of Christianity in the State of Georgia,” to reach destitute members in different parts of the state and arrange for the distribution of prayer books and religious tracts.

In February 1823, the three Episcopal congregations in Georgia–Christ Church in Savannah, Saint Paul’s in Augusta, and Christ Church Frederica on St. Simons Island–sent delegates to the first convention of what became the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of Georgia. They celebrated the Eucharist together and prayed Morning Prayer daily through the February 24-28 convention. The delegates elected a Standing Committee, deputies to the General Convention of the Episcopal Church, and wrote the Constitution and Canons for the Diocese. They also founded “The Protestant Episcopal Society for the General Advancement of Christianity in the State of Georgia,” to reach destitute members in different parts of the state and arrange for the distribution of prayer books and religious tracts. The Address went on to say, “We are aware, brethren, that there are difficulties to be encountered. Your number is small, and the individuals composing that number, are perhaps scattered. But be not disheartened. These obstacles are not insurmountable….However small, then, be your number in each vicinity, let that small number be embodied.”

The Address went on to say, “We are aware, brethren, that there are difficulties to be encountered. Your number is small, and the individuals composing that number, are perhaps scattered. But be not disheartened. These obstacles are not insurmountable….However small, then, be your number in each vicinity, let that small number be embodied.” After the Diocese of Georgia was organized, the South Carolina Bishop presided at Georgia Conventions until a Bishop was elected for Georgia. It would be two years before the Diocese would add its fourth congregation, Christ Church in Macon. At that 1825 meeting, they noted in the minutes a letter from the Honorable C.B. Strong of Macon that said, “You know, by the short tour you have made through the State, the forlorn and scattered situation of the almost lost sheep of our flock—their destitute and bewildered condition; and how little is known of our holy faith and sublime mode of worship….These considerations prompt me to entreat you to use your greatest exertions to induce the Convention, either by application to the General Convention, or in some other way, to procure one Missionary or more, to preach in this State.”

After the Diocese of Georgia was organized, the South Carolina Bishop presided at Georgia Conventions until a Bishop was elected for Georgia. It would be two years before the Diocese would add its fourth congregation, Christ Church in Macon. At that 1825 meeting, they noted in the minutes a letter from the Honorable C.B. Strong of Macon that said, “You know, by the short tour you have made through the State, the forlorn and scattered situation of the almost lost sheep of our flock—their destitute and bewildered condition; and how little is known of our holy faith and sublime mode of worship….These considerations prompt me to entreat you to use your greatest exertions to induce the Convention, either by application to the General Convention, or in some other way, to procure one Missionary or more, to preach in this State.” After her husband died in 1746, Hastings increasingly connected with Methodism through the Rev. John Wesley, who she met after his return from Georgia. In published letters, Wesley credited the Countess with convincing him to preach to miners in the open air, telling him “They have churches, but they never go to them! And ministers, but they seldom or never hear them! Perhaps they might hear you.” He tried her plan and found his preaching transformed.

After her husband died in 1746, Hastings increasingly connected with Methodism through the Rev. John Wesley, who she met after his return from Georgia. In published letters, Wesley credited the Countess with convincing him to preach to miners in the open air, telling him “They have churches, but they never go to them! And ministers, but they seldom or never hear them! Perhaps they might hear you.” He tried her plan and found his preaching transformed. Her views on slavery were inconsistent and her work in Savannah was part of that story. She promoted the freedom of formerly enslaved Africans and supported publication of two slave narratives, written by Ukawsaw Gronniosaw and Olaudah Equiano. Those 1700s memoirs published in England were the first time those in Britain heard of life directly from those who had been enslaved. On Whitefield’s death in 1770, she inherited his estates in Georgia and South Carolina, including the Bethesda Home for Boys and some enslaved persons who worked at the home. She then added to their number, approving the purchase of more enslaved persons to work at Bethesda. She continued to support and oversee the orphanage until the newly formed State of Georgia confiscated the property after the Revolution.

Her views on slavery were inconsistent and her work in Savannah was part of that story. She promoted the freedom of formerly enslaved Africans and supported publication of two slave narratives, written by Ukawsaw Gronniosaw and Olaudah Equiano. Those 1700s memoirs published in England were the first time those in Britain heard of life directly from those who had been enslaved. On Whitefield’s death in 1770, she inherited his estates in Georgia and South Carolina, including the Bethesda Home for Boys and some enslaved persons who worked at the home. She then added to their number, approving the purchase of more enslaved persons to work at Bethesda. She continued to support and oversee the orphanage until the newly formed State of Georgia confiscated the property after the Revolution. James Edward Oglethorpe sent a party up the Savannah River in 1735 to build a fort as a refuge for settlers living near the first set of rapids. Oglethorpe named Fort Augusta for the princess who would become the mother of George III. In time, the trading post prospered. In April of 1750, the people who lived and traded in this area erected a church. Noting that their friendship with the indigenous population was “sometimes precarious,” they built the church under the shelter of the Fort.

James Edward Oglethorpe sent a party up the Savannah River in 1735 to build a fort as a refuge for settlers living near the first set of rapids. Oglethorpe named Fort Augusta for the princess who would become the mother of George III. In time, the trading post prospered. In April of 1750, the people who lived and traded in this area erected a church. Noting that their friendship with the indigenous population was “sometimes precarious,” they built the church under the shelter of the Fort. The first report from Mr. Copp came six months later when he asked for a transfer to a church in South Carolina. He did say that 80-100 people a week attend divine worship and he had baptized 30 from both Georgia and South Carolina. But he added, “Here we have been under continual fears and apprehensions of being murdered and destroyed by the [native inhabitants] there being no one within 140 miles capable of lending us any assistance in times of danger—so far are we situated in the wild, uncultivated wilderness.” He was not granted the transfer for three years.

The first report from Mr. Copp came six months later when he asked for a transfer to a church in South Carolina. He did say that 80-100 people a week attend divine worship and he had baptized 30 from both Georgia and South Carolina. But he added, “Here we have been under continual fears and apprehensions of being murdered and destroyed by the [native inhabitants] there being no one within 140 miles capable of lending us any assistance in times of danger—so far are we situated in the wild, uncultivated wilderness.” He was not granted the transfer for three years. Zouberbuhler was appointed on All Saints’ Day, 1745, by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), to be pastor of Christ Church in Savannah. Bartholomew was the son of a native Swiss pastor who had originally served congregations of Swiss Protestants in the colony of South Carolina and then had become pastor of an Anglican parish there. Bartholomew, believing himself called to the ministry, made the long trip across the ocean to be ordained by the Bishop of London.

Zouberbuhler was appointed on All Saints’ Day, 1745, by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), to be pastor of Christ Church in Savannah. Bartholomew was the son of a native Swiss pastor who had originally served congregations of Swiss Protestants in the colony of South Carolina and then had become pastor of an Anglican parish there. Bartholomew, believing himself called to the ministry, made the long trip across the ocean to be ordained by the Bishop of London. Zouberbuhler’s concern was not only for Christians of other languages and church traditions who had settled in Georgia, but for all the inhabitants, including enslaved persons from Africa. At Christ Church in 1750, he baptized the first enslaved African to be baptized in the colony. When Zouberbuhler died, he left a sizable portion of his estate as a trust to be used to employ qualified teachers “to teach Anglican Christianity to Negroes.” He is buried in Savannah’s Bonaventure Cemetery.

Zouberbuhler’s concern was not only for Christians of other languages and church traditions who had settled in Georgia, but for all the inhabitants, including enslaved persons from Africa. At Christ Church in 1750, he baptized the first enslaved African to be baptized in the colony. When Zouberbuhler died, he left a sizable portion of his estate as a trust to be used to employ qualified teachers “to teach Anglican Christianity to Negroes.” He is buried in Savannah’s Bonaventure Cemetery. Though his legacy as the founder of the Methodist movement has born so much good fruit for almost three centuries, John Wesley’s ministry in Georgia went catastrophically wrong. Wesley arrived to a Savannah that was still a village of just two hundred houses. In less than two years, a 44-person grand jury, making up a significant percentage of the population, would approve a 10-count indictment against their idealistic minister.

Though his legacy as the founder of the Methodist movement has born so much good fruit for almost three centuries, John Wesley’s ministry in Georgia went catastrophically wrong. Wesley arrived to a Savannah that was still a village of just two hundred houses. In less than two years, a 44-person grand jury, making up a significant percentage of the population, would approve a 10-count indictment against their idealistic minister. Wesley who had afflicted others with a rigid approach to religion was surprised by the grace of a God who knew John’s heart was altogether corrupt and abominable and yet loved the imperfect parson anyway. John would go on to travel a quarter of a million miles on horseback, delivering more than 40,000 sermons, and founding the Methodist Movement boasting 541 preachers and 135,000 members in his lifetime. There are 80 million Methodists around the world today who have found their hearts warmed by the grace John Wesley experienced.

Wesley who had afflicted others with a rigid approach to religion was surprised by the grace of a God who knew John’s heart was altogether corrupt and abominable and yet loved the imperfect parson anyway. John would go on to travel a quarter of a million miles on horseback, delivering more than 40,000 sermons, and founding the Methodist Movement boasting 541 preachers and 135,000 members in his lifetime. There are 80 million Methodists around the world today who have found their hearts warmed by the grace John Wesley experienced. Coosaponakeesa of the Wind Clan was essential to the success of the Colony of Georgia. Born in 1700 in the Lower Creek Nation’s Capitol of Coweta, she was the daughter of Edward Griffin, an English trader, and a Creek woman usually referred to as Brim, which was also the name of her relative who ruled the Creek Nation. By the time of her death in 1765, she was the largest landowner and the wealthiest person in the colony.

Coosaponakeesa of the Wind Clan was essential to the success of the Colony of Georgia. Born in 1700 in the Lower Creek Nation’s Capitol of Coweta, she was the daughter of Edward Griffin, an English trader, and a Creek woman usually referred to as Brim, which was also the name of her relative who ruled the Creek Nation. By the time of her death in 1765, she was the largest landowner and the wealthiest person in the colony. Jacob Matthews died in 1745. With her third marriage in 1747, Mary became the wife of the Rector of Christ Church in Savannah, the Rev. Thomas Bosomworth. The two became a power couple with strong connections in both Creek and British society. They pressed their land claim in a ten-year battle, traveling to England at one point to meet with the British Board of Trade. In 1759, a compromise resolved the issue. The Board of Trade auctioned off Sapelo and Ossabaw Islands, giving the proceeds to Mary. The land sold for £2,100, which would be worth more than half a million dollars today. She was also permitted to keep St. Catherine’s Island “in consideration of services rendered by her to the province of Georgia.” Mary moved to the island in 1760 and lived her remaining five years there.

Jacob Matthews died in 1745. With her third marriage in 1747, Mary became the wife of the Rector of Christ Church in Savannah, the Rev. Thomas Bosomworth. The two became a power couple with strong connections in both Creek and British society. They pressed their land claim in a ten-year battle, traveling to England at one point to meet with the British Board of Trade. In 1759, a compromise resolved the issue. The Board of Trade auctioned off Sapelo and Ossabaw Islands, giving the proceeds to Mary. The land sold for £2,100, which would be worth more than half a million dollars today. She was also permitted to keep St. Catherine’s Island “in consideration of services rendered by her to the province of Georgia.” Mary moved to the island in 1760 and lived her remaining five years there. Growing up in the house next door to King George’s Whitehall Palace, James Edward Oglethorpe was the youngest of ten children born to a prominent English family. Inheriting a family estate at 26, the up-and-coming Oglethorpe ran for the House of Commons. Reports say soon after the election, Oglethorpe was already drunk when he wandered into a tavern at six o’clock in the morning. He got into a heated exchange over politics with a lamplighter and killed the man in the fight that followed. A powerful friend intervened to get Oglethorpe freed from jail.

Growing up in the house next door to King George’s Whitehall Palace, James Edward Oglethorpe was the youngest of ten children born to a prominent English family. Inheriting a family estate at 26, the up-and-coming Oglethorpe ran for the House of Commons. Reports say soon after the election, Oglethorpe was already drunk when he wandered into a tavern at six o’clock in the morning. He got into a heated exchange over politics with a lamplighter and killed the man in the fight that followed. A powerful friend intervened to get Oglethorpe freed from jail. Living into the motto of Georgia’s Trustees—Non sibi sed aliis (Not for self, but for others)—Oglethorpe remained a tireless idealist. He wholly opposed slavery in Georgia and kept an enlightened approach in relations with the indigenous population. (The painting above shows Tomochichi and other Yamacraw visitors, being presented to the Georgia Trustees in London by James Edward Oglethorpe in 1734.)

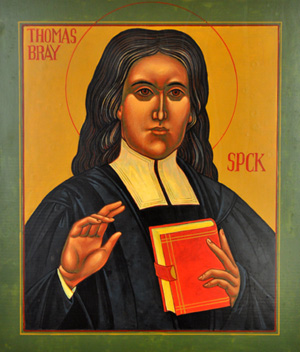

Living into the motto of Georgia’s Trustees—Non sibi sed aliis (Not for self, but for others)—Oglethorpe remained a tireless idealist. He wholly opposed slavery in Georgia and kept an enlightened approach in relations with the indigenous population. (The painting above shows Tomochichi and other Yamacraw visitors, being presented to the Georgia Trustees in London by James Edward Oglethorpe in 1734.) Weekly Beef and Beer Dinners hosted in Newgate Prison by the Rev. Thomas Bray are where the priest planted seeds for what grew into the Colony of Georgia. Bray (1656-1730), who was then the Rector of St. Botolph-Without-the-Walls in London, was deeply concerned about those jailed for their inability to pay off their debts. Through this work, the charismatic priest gathered a group of friends including a young politician, James Edward Oglethorpe. Bray dreamed of a colony where those trapped in debt could gain the opportunity for a fresh start. While the dedicated reformer died before Georgia was founded, the charter for the colony captured his utopian ideal with prohibitions against selling rum, having enslaved people work the land, and owning more than 150 acres per family. The charter also had a prohibition against lawyers and expressed tolerance for Jews as well as some persecuted Christian groups (such as the Salzburgers) to settle. This Christian idealism was the driving force for the founders of the colony. (Louise Shipps painted the icon above. The original painting of Sir Thomas Bray is in the conference room at Diocesan House.)

Weekly Beef and Beer Dinners hosted in Newgate Prison by the Rev. Thomas Bray are where the priest planted seeds for what grew into the Colony of Georgia. Bray (1656-1730), who was then the Rector of St. Botolph-Without-the-Walls in London, was deeply concerned about those jailed for their inability to pay off their debts. Through this work, the charismatic priest gathered a group of friends including a young politician, James Edward Oglethorpe. Bray dreamed of a colony where those trapped in debt could gain the opportunity for a fresh start. While the dedicated reformer died before Georgia was founded, the charter for the colony captured his utopian ideal with prohibitions against selling rum, having enslaved people work the land, and owning more than 150 acres per family. The charter also had a prohibition against lawyers and expressed tolerance for Jews as well as some persecuted Christian groups (such as the Salzburgers) to settle. This Christian idealism was the driving force for the founders of the colony. (Louise Shipps painted the icon above. The original painting of Sir Thomas Bray is in the conference room at Diocesan House.) As we approach the bicentennial of our founding in 2023, we will share the story of the Diocese of Georgia. Looking back on our Centennial Celebration on April 22, 1923, the tone was laudatory. The fourth Bishop of Georgia, the Rt. Rev. Frederick Focke Reese (pictured here in the bishop’s chair that was in the sanctuary at Christ Church, Savannah) preached a sermon that praised his predecessors with words that made them seem so heroic as to not be real:

As we approach the bicentennial of our founding in 2023, we will share the story of the Diocese of Georgia. Looking back on our Centennial Celebration on April 22, 1923, the tone was laudatory. The fourth Bishop of Georgia, the Rt. Rev. Frederick Focke Reese (pictured here in the bishop’s chair that was in the sanctuary at Christ Church, Savannah) preached a sermon that praised his predecessors with words that made them seem so heroic as to not be real: On February 24-28 in 1823, Saint Paul’s in Augusta hosted the First Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of Georgia. Clergy and lay persons from Christ Church in Savannah and Christ Church Frederica on St. Simons Island joined the delegates from Augusta in forming this Diocese. We would not be able to call our first bishop until we had the six congregations required by the Canons of the Episcopal Church. That election happened in 1841, with the Bishop of South Carolina making visitations in the intervening years.

On February 24-28 in 1823, Saint Paul’s in Augusta hosted the First Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of Georgia. Clergy and lay persons from Christ Church in Savannah and Christ Church Frederica on St. Simons Island joined the delegates from Augusta in forming this Diocese. We would not be able to call our first bishop until we had the six congregations required by the Canons of the Episcopal Church. That election happened in 1841, with the Bishop of South Carolina making visitations in the intervening years.